Ogunde Tremayne had trouble accepting himself and his sexuality. But then he found RuPaul’s Drag Race.

Middle school was a tough time for Ball State University sophomore Ogunde Tremayne. He had so many questions: How do you ask a guy out? How do you go on a date? What does being gay really mean?

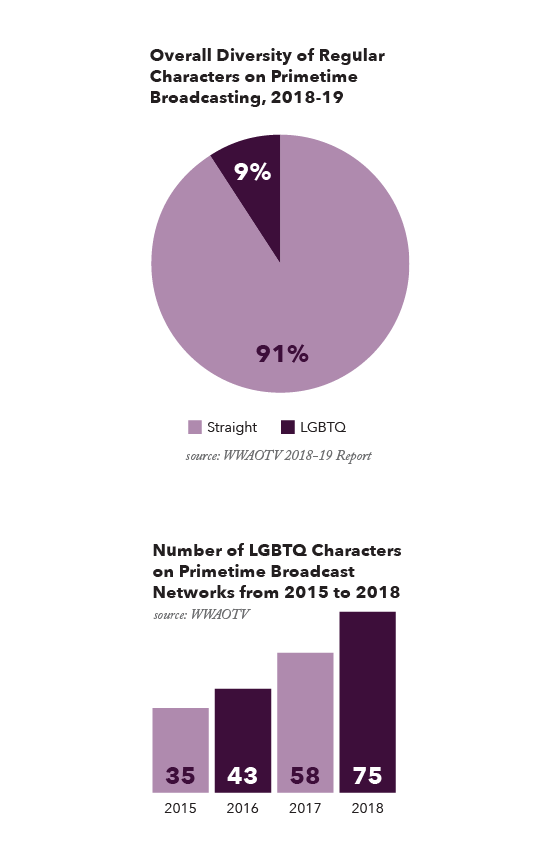

He never saw LGBTQ relationships on TV, so he thought it must be wrong. Or, maybe it wasn’t. He was through lying to himself and suppressing who he was, so he researched online. Then he found RuPaul’s Drag Race, a reality competition with weekly challenges to find a drag superstar.

Ogunde would sneak into his mom’s room and watch the show. But he had to be careful: There was a feature on the TVs in his house that could display what the other TVs were playing.

He’d watch the show whenever he could and record it when he couldn’t. He was always scared his grandmother or uncle would find the recording of the show.

For the first time, he saw gay people like him on TV. There were gay men being artistic, and it was educational. They would talk about safe sex and navigating the world as a member of the LGBTQ community. Through the show, Ogunde finally felt connected to his community.

According to the academic article “GLBTQ Cinema,” until the 1970s, queer characters were portrayed without explicitly showing their sexualities.

For example, gay men were shown as effeminate, while lesbians were represented as butchy. Because viewers might not have known someone who identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender, the cinematic representations could fuel further stereotypes, homophobia, or prejudice.

Ogunde says all he usually sees on TV is typical male and female gender roles. Even in the gay community, he says, there is the idea of “who’s the man and who’s the woman” of the relationship. He says the labeling is relentless, and there is a stigma against acting “unmanly.” Ogunde says this puts emphasis on conforming when you should be true to yourself.

According to an article written by Omotayo Banjo in the Penn State McNair Journal, people constantly compare how they are treated to their perceptions of how they deserve to be treated. And the perceptions of what we deserve largely come from gender socialization, parents, and the media.

Sara Collas, an assistant teaching professor of sociology at Ball State who specializes in gender studies, says media often distort the perception of what people should want. Couples might be depicted as blissful on TV, while many real-life relationships end up failing. She says the dominant media present couplehood as the primary goal, and people living content single lives are rarely portrayed.

Sara Collas, an assistant teaching professor of sociology at Ball State who specializes in gender studies, says media often distort the perception of what people should want. Couples might be depicted as blissful on TV, while many real-life relationships end up failing. She says the dominant media present couplehood as the primary goal, and people living content single lives are rarely portrayed.

Collas believes the idea that you are only complete if you’re in a relationship does a real disservice to people, saying it’s “brainwash” to think you can’t be happy alone. She believes self-love is the most important thing.

Ogunde knew a lot of his happiness relied on self-acceptance. He remembers telling himself at the end of every episode of RuPaul’s Drag Race, ‘If you can’t love yourself, how in the hell you gonna love somebody else?’

Around the same time, Ogunde discovered coming out videos on YouTube. Watching people come out to their parents and be accepted meant so much to him. It was bittersweet, though, to watch others do what he’d only dreamt about. Seeing someone have the courage to do that, and then post it online to help give the courage to others, was empowering for Ogunde. It really made him want to come out, and in seventh grade, he did.

In a study published in Behaviour and Information Technology, researchers identified reasons for LGBTQ members to reveal their sexual orientations. These included improving relationships, improving their own mental health, and helping change society’s attitude on the community. But the coming out videos fall into a fourth category—to support others who are going through the same thing.

Channels like YouTube and Logo TV, which became known for having gay characters and themes, helped Ogunde come to accept who he is.

This column was originally published in the spring 2019 print edition.