After 24 years of marriage, Stuart Hargis says divorce was the best thing to happen to him and his ex-wife.

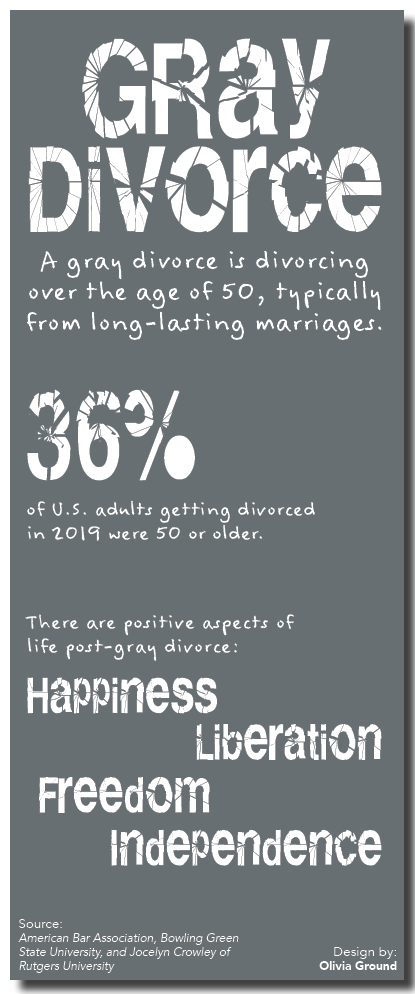

Stuart married his ex-wife in 1978 after they met as coworkers, a marriage that would last until they filed for divorce in 2002. Stuart’s divorce falls under the gray divorce, a term coined by the American Bar Association defined as divorcing over the age of 50, typically from long-lasting marriages

This phenomenon is reality for many couples.

A study by the Department of Sociology at Bowling Green State University reports that 36% of United States adults getting divorced in 2019 are 50 or older. In 1990, only 8.7% of divorces in the U.S. occurred among adults aged 50 or older. Researchers theorize that this massive increase is due to changing views across generations, the financial stability of women, and incompatibility.

Life expectancy and societal view

Experts across the U.S. are searching for the reasons behind this significant increase in gray divorce. Many speculate that longer life expectancy may play a role.

According to the American Psychological Association, increased life expectancy may mean decades of good health with a spouse, something that many cannot picture.

Staying in an “empty shell” marriage, meaning poor quality or lacking in connection, means having added stress and conflict while aging. Additionally, a longer life expectancy means couples can divorce in their later years and still have the chance to live a healthy, fulfilling life.

Stuart says he and his ex-wife stayed together longer than they should have out of consideration for their son. Stuart couldn’t imagine living another 30 years with his spouse and knew their time had come and gone.

“I really did care for her, all but the last year and a half or two years,” he says. “There was just nothing there. I didn’t want anything bad to happen to her, I just didn’t want to be there anymore.”

Older generations see marriage as a pillar of society, whereas younger people are more likely to embrace cohabitation, being a single parent, or being divorced.

This may be due to the Baby Boomer generation, as they are the second largest generation and entering older age. Many Boomers are in their second or third marriage, which may contribute to the increasing gray divorce rate, as individuals who remarry after a divorce are more likely to divorce again, known as the “divorce echo effect.”

Ball State professor Scott Hall teaches and researches within the Department of Early Childhood, Youth, and Family Studies. Hall has published multiple studies about marital beliefs and marriage adjustment.

“People have a lot of life left to live, so starting over or being single wouldn’t be as intimidating,” Hall says.

Hall believes younger people’s attitudes toward marriage may impact older people’s beliefs.

“There are changing social norms where older people are being influenced by younger people,” he says. “Our current age has a big focus on mental health; there’s a sense of ‘You have to take care of yourself.’ I think that filters up to the older generations.”

Women in the workforce and finances

Researchers also believe the increase in women in the workforce impacts gray divorce. This societal trend means women are more likely to be able to financially support themselves. Previously, men were the breadwinners of the household, thus women didn’t often consider a divorce because they feared a loss of income.

In modern times, women can now support themselves, enabling them to leave abusive or

conflict-filled marriages.

While the pay gap still exists, more women are making more money, per a 2022 Pew Research study that details the 22 major U.S. cities where young women are earning as much as their male counterparts.

Financial independence allowed Leah Howard to divorce her husband after 36 years of marriage.

Leah supported her husband throughout their marriage as she climbed the ladder working in management for a fast food chain. After years of working, Leah and her spouse bought a liquor store and operated it together for many years. She recalls working 70 or 80-hour work weeks, maintaining their income and achieving their goals of building their own home.

In 2020, when she filed for divorce, she was never worried about the money, but instead she was concerned about the workload of the liquor store.

“I mean the last 13 years were so hard, nothing but working that store,” she says. “Financially, I wasn’t afraid. I was scared about the workload.”

She held onto the store for two years following the divorce until she received an offer and decided to sell. Leah divorced her husband and maintains a comfortable life because of the money she had made earlier in life. She remained in their house and now works at a local sheriff’s office.

“My mom used to always say she couldn’t divorce, she hadn’t worked since getting married,” Leah says. “When I was young, a woman needed a man, but that’s not reality anymore.”

Additionally, those going through gray divorce have likely accrued much more than younger couples. Thus, splitting wealth, possessions, or other assets may prove difficult, particularly with retirement looming.

Lingering issues and communication

Some marriages find themselves slowly fizzling after long unresolved issues. After Stuart spent a short time in the hospital, his confidence couldn’t quite recover.

“A lot of the things that attracted her to me in the first place, my can-do attitude, … it would take years for me to get that back,” he says.

This unexpected life event slowly drove a wedge between the two of them and led to a lack of communication. When Stuart was recovering, his spouse had difficulty believing he was still capable.

“We didn’t have the long talks that we used to,” Stuart says. “We really didn’t communicate much at all. The last four to five years, we didn’t even sleep in the same room. It was a very rough time.”

After 10 years of marriage, Leah and her ex-husband took a four to five month break.

“I think he just didn’t feel happy anymore,” she says. “I was always a fixer, but you can’t always be a savior. Sometimes people have to struggle.”

Leah described this time in their relationship as a “really dark place.”

Empty nest and loneliness

The tension in Stuart’s marriage led to a breaking point in 2002 when their son started college.

As soon as Stuart and his spouse became “empty nesters,” or parents with children who have grown and moved away, his spouse filed for divorce. Stuart reported that the most challenging part of his divorce was the distance that grew between him and his son.

According to an article by the National Center for Family and Marriage Research, parent-child disconnectedness adds another blow to parents healing from divorce. Gray divorce presents unique challenges regarding children, as they are usually older or even adults. Stuart feels his son should make more of an effort to reach out.

Stuart says he hears from his son maybe three to four times a year.

“There’s nothing he could ever do that is going to change the way I feel about him,” he says.

Stuart also notes that losing mutual friends and family following divorce was an unexpected challenge.

“A lot of what you consider your really closest best friends disappear,” he says. “All of the rest of the friends we had as a couple, I haven’t heard a word out of any of them.”

And yet it’s worth it

Following his divorce, Stuart consulted with some of his coworkers for advice. One of them told him to “just give it time. There’s life after divorce.”

“A lot of people think they’re losing ‘the one,’ and they go into a depression and are never the same,” Stuart says.

According to a study conducted by Jocelyn Crowley of Rutgers University, participants identified positive aspects of their lives post-gray divorce, including higher levels of overall happiness, liberation from their ex-spouses, and enhanced independence and freedom.

Hall believes communication is the foundation to maintaining a connection because people change and grow throughout the marriage.

“Something I teach in my classes is that it’s like trying to walk up an escalator that’s going down,” he says. “As soon as you stop, you hit the ground. Regardless of how long someone has been together, effortful conversation is still needed.”

Leah credits much of her post-divorce happiness to counseling. After her split, she sought out a counselor to help her navigate the next stages of her life. Leah believes everyone should try counseling.

“I’m very thankful,” she says. “At first, I was afraid to be alone, but I finally have my own space and things.”

Hall advises those going through a gray divorce to be patient with themselves.

“Your identity has been weaving with someone else’s, so it may take a while,” he says. “That new identity formation will take some time, so find some positive contributions to wind your identity around to have purpose and meaning.”

In terms of navigating a split with children, Hall recommends an open channel of communication and possibly seeking counseling if necessary.

“A marriage ending is a death, but now I get to figure out new things I want,” Leah says. “You don’t know you’re not happy until you find something different.”

Sources: American Bar Association, Bowling Green State University, Oxford Academic, Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, American Bar Association, Pew Research Center, Pew Research Center, National Center for Family and Marriage Research, Rutgers University, American Psychological Association