Changing times don’t have to bring a change in our neighborhoods.

What is a neighbor? Sometimes, a neighbor is a person who you trust to watch the dog while you’re on vacation. Other times, a neighbor may be someone who you occasionally acknowledge with a head nod before driving off to work. The concept of a neighbor, and neighborhoods in general, can vary from person to person and can shift over time.

According to Jennifer Erickson, anthropology professor at Ball State and a member of the Muncie Neighborhood Board Association, a neighborhood consists of certain core values. These values differentiate the concept of a neighborhood from a group of houses living together.

“Neighborhoods are made of people that come together to work on and improve the place that they’re living in. They care about it enough to put time and energy into getting to know one another, building a community, and having social events together,” Erickson says. “Good neighborhoods are diverse, welcoming, and safe.”

Bonnie Buuck, who has lived in a little neighborhood in Ossian, Ind., for more than 45 years, shares Erickson’s expert analysis. Located in northeast Indiana, Ossian is a quaint city with a population just under 3,500.

“Neighborhoods are more of a community type thing because it doesn’t necessarily have to be neighbors right next to you. When you’re coming down a road and you get stuck in the snow, neighbors are the ones who usually try to help. We’ve done that many times. To help somebody is what makes a ‘neighbor,’” says Bonnie.

As many neighbors have moved in and out of houses over the years, Bonnie has tried to keep creating a sense of community, reminiscent of what she remembers when she was younger.

“I do a lot of walking. When I was younger, I loved bicycle riding. I’ll go out and say hi, and we talk quite a while,” says Bonnie. “We’ve always made a point of talking to people and enjoying their company.”

Bonnie explains her belief that neighborhoods are built upon the foundation of helping one another and her community. She recalls an instance nearly two decades ago in which she and her husband, Ron, had to help a young man out from a ditch after he slid off the road while driving. She still remembers seeing the small gray car flipped on its roof and feeling relieved that nobody was hurt.

“We just wanted to help,” says Bonnie.

Bonnie and her neighbors strive to get to know one another and preserve a safe environment by addressing previous problems within the community. Over time, she has seen an improvement in driving accidents because of the neighborhood’s efforts to get a stop sign on her road.

“The people driving will just think they have the right away, and they will run into each other even if they saw each other. We called a radio station. They came out here and did an article on our corner to tell people how hard it was to see, so the states put in a stop sign one way, which really curtailed that problem,” Bonnie recalls.

Neighborhood culture is centered around improving the environment in which certain people live. But the rising crime rates across the U.S. have stunted the hard work people put into their communities.

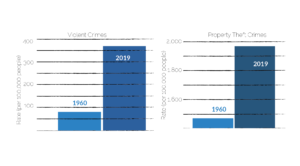

For instance, the Disaster Center lists the Indiana crime rates from 1960 to 2019. There is an increase of violent crimes rising from 84.6 victims every 100,000 people in 1960 to 370.8 victims every 100,000 people in 2019. Similarly, the amount of property theft rose from 1,469.1 victims every 100,000 people in 1960 to 1,971.0 victims every 100,000 people in 2019.

Bonnie says that she and her fellow neighbors have seen a sharp rise in criminal activity in their neighborhood.

“I don’t remember much of any [crime] when we were first here. And gradually, it just kind of keeps getting worse,” she says. “My brother-in-law has had stuff stolen, and I don’t really think there’s any cause to it. Just like everywhere else, if many people think they can get away with it, they will try something.”

But what caused this rise in crime rates? Karley Dishmon, a student at Ball State and lifetime resident of Muncie, blames poverty, as well as general rebelliousness.

“It is worse for younger generations now actually, specifically in my generation. These kids that are dying and doing these drive-bys. They’re like my age, and I don’t know if it’s just because we’re hitting that adult stage, they’re just trying to show off, or the tensions in their daily lives,” Karley says. “I personally have grown up living off food stamps for many, many years. I’ll be honest, I don’t really know the financial situations of others but it would probably be exactly the same as my neighbors.”

Many communities have faced a change in industry and commerce, thus creating a rise in economic instability. According to Erickson, this change can be seen in Muncie as well.

“Fifty years ago, [Muncie neighborhoods were] primarily family neighborhoods with professionals. There was a factory in that neighborhood that people remember. Over time as industry decreased in Muncie, Ball State and Ball Memorial Hospital became the primary employers,” Erickson says.

Karley agrees, declaring that Muncie specifically has been economically disadvantaged due to the closing of many factories that caused neighborhoods to thrive.

Even in Bonnie’s community, there are many people moving in and out of homes due to the declining demand for the farm and factory work that her neighbors produce, as well as the rising expenses.

“There’s probably a few people that have gone bankrupt and had to sell out. And, just like how most things go, people die and the new ones take over,” Bonnie says. “So some can’t afford to stay here, and they leave us when they have to look for other work. Some will do both and work uptown and farm within the community, until they can get enough built up to be able to buy their own home.”

With the loss of many neighbors within a community, the importance of sticking together becomes more prominent. When inequality rises and people become more vulnerable, neighborhoods must come together in support.

“I know that the moratorium on eviction notices has benefited a lot of people. The federal government saying you can’t kick people out during a pandemic is really important, and I think speaks to just how vulnerable people are to the processes of jobs and housing and healthcare. And that economic inequality is this kind of driver of a lot of these social problems,” Erickson says.

However, while neighborhoods across the U.S. are facing economic challenges, rising crime rates, and a global pandemic, some people still value having a close-knit community. Karley shares a story about her neighborhood rallying around a family in support.

“One of my neighbors just lost his 19-year-old daughter to COVID. The thing about Black communities is that when specifically they lose a loved one, they come together. I can’t tell you how many days in a row my neighborhood was full of cars, because this entire community came to one house to give him love. Like it is the most loving community I think I’ve ever met in my life,” Karley says. “You just saw tons of people rallying together for days on end bringing in food, bringing in love and whatnot.”

Stories like Karley’s prove that some people are still as neighborly as ever, reaching out to lend hands or provide moral support. Rising statistics will not stop people from building communities where they can find a sense of home.

Sources: Disaster Center

Images: Sabine Croy

Featured Image: Sabine Croy