Underwater metropolis

Located in oceans along the equator, there are millions of coral that act as a sanctuary for tropical fish and hunting spots for fishermen. These reefs are home to a diverse range of wildlife and attract scuba divers and tourists who frequently visit them in the depths.

At the age of 22, Sheli Plummer moved to the Florida Keys to dive in the reefs. It was her dream to identify every fish in its waters and understand their behaviors in their aquatic environments. She would swim through the reefs studying fish mating rituals, territorial disputes, and symbiotic relationships. Many of these relationships are directly connected to the corals themselves: beautiful creatures that come in many colors and paint the oceanic landscape.

At present, Plummer is an associate lecturer of kinesiology at Ball State University, and she teaches courses in physical wellness and scuba. To this day, she continues to visit reefs with her students, and she sees firsthand the reefs’ rapid deterioration rate. These underwater paradises are at risk of disappearing due to the extreme environmental changes affecting our oceans.

Threats to coral

Plummer explains that coral can indicate when an environment is drastically affected by climate change as they can only survive at specific temperatures, and with global warming heating the waters above 90 F, corals are struggling for survival.

“In the winter, it gets down to 65 F and up to 85 F in the summer,” Plummer says. “If it got much colder or any warmer, then they have trouble.”

The National Ocean Service for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration explains that rising temperatures cause the corals to turn white and die in large quantities. This is a phenomenon known as coral bleaching. Extreme heat forces symbiotic organisms, crucial to the coral’s survival, to leave.

“Inside the coral animal is an algae,” Plummer says. “They live in a symbiotic relationship. The algae creates oxygen for the coral …, the coral pulls in the food.”

Plummer explains that algae is what gives coral its colors. When the water temperature becomes too hot, the algae leaves, causing the coral to turn white. She says coral bleaching is a major threat to coral reefs, especially in the Florida Keys.

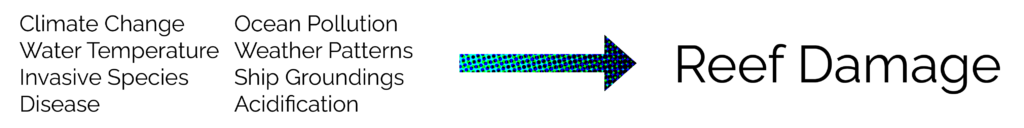

According to “Restoring Coral Reefs,” a report by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the global coral reef population is at risk of going extinct by the end of the century. At present, the world has already lost 30% to 50% of its coral populations. Many factors are at fault for reef damage: climate change, water temperature changes, invasive species, coral diseases, ocean pollution, acidification, weather pattern changes, and impacts from ship groundings. The majority of these factors are due to human interference with the environment, such as contributions to ocean pollution and atmospheric greenhouse gasses.

Emily Pax, a Ball State undergraduate student majoring in geoscience, is a member of the Green Action Team (GAT). In this club, Emily learns about environmental issues and how local communities contribute to global pollution. Two types of pollution that impact both inland rivers and tropical coastlines are industrial and agricultural runoff.

“I learned that there are these contamination plumes in groundwater that travel underground, and there is the mid-continental split,” Emily says. “On one side of the continent, groundwater flows toward the Atlantic and the other to the Pacific … Any kind of contaminant that gets in the groundwater … it will slowly make its way out to sea.”

Paul Venturelli, an associate professor of fisheries at Ball State, adds that a lot of runoff and pollution that is dumped into waterways is often placed there intentionally. This pollution can seep into the groundwater or contaminate waterways that lead into the ocean.

“[Water is] used for waste disposal,” Venturelli says. “We put sewage into our waterways, and that is on purpose … Microplastics are coming in through that pathway as well as chemicals.”

Not only do contaminants pose a threat to ocean environments, but tons of plastic also cause problems for aquatic organisms. According to research by Our World in Data, the world has a staggering 450 million tons of plastic, and plastic production only continues to increase. One million to 2 million tons of plastic are dumped into the ocean per year, and this plastic makes it into the reef systems.

Water temperature changes and water composition are what ultimately determine how healthy a reef is. When environmental factors start pushing their limits, coral bleaching is not far away.

Why coral matters

Coral reefs are famous for the diverse creatures they host. According to “The Importance of Coral Reefs,” a coral tutorial by the NOAA, the biodiversity found in reefs might be the key to developing new medicines for the 21st century. Genetic material from coral reef organisms currently helps medics study cures for cancer, arthritis, bacterial infections, and various viruses.

Not only do reefs help develop life-changing products for consumers, the NOAA tutorial also states that reefs contribute over $100 million to United States fisheries annually. This does not include the billions of dollars businesses make recreationally through guided scuba tours, fishing, restaurants, hotels, and other tourist attractions. They make up a huge chunk of the global economy because of their diverse resources.

Coral restoration

Because the Earth’s climate is changing, coral conservation scientists have had to improvise new ways to increase coral populations. To combat coral bleaching and reef deterioration, conservationists are taking extra steps to ensure coral reefs, new and old, have healthy habitats.

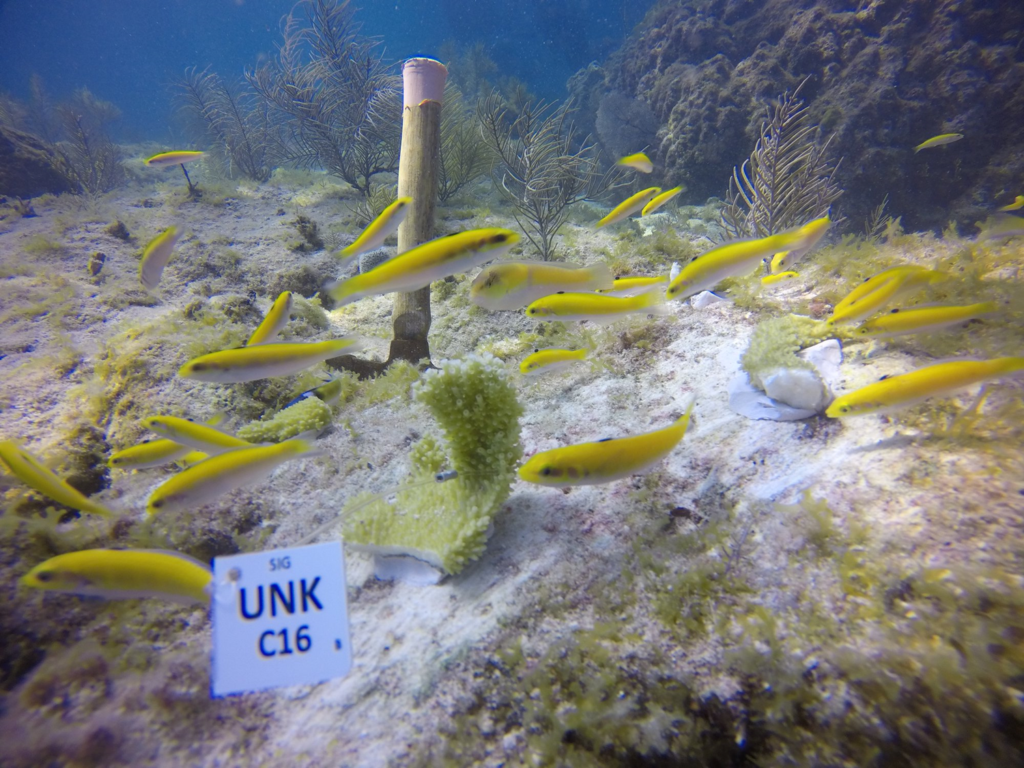

In the summer of 2018, Plummer joined the Coral Restoration Foundation in the Florida Keys to help them grow baby corals and plant them in safe habitats.

“They grow corals in a nursery, and the nursery contains these trees made out of PVC and monofilament line,” Plummer says. “They grow thousands of corals and then take them out and plant them.”

According to the NOAA, conservation efforts provide more than 40,000 corals throughout the Caribbean each year. Researchers find suitable habitats for growing baby coral and work to transform those habitats into coral nurseries.

What we can do

There are many small actions communities can take to make a difference. People can recycle, limit water usage, use biodegradable products, limit how much plastic they use, carpool when possible, and use public transit.

Venturelli studies how human interference alters the environment and the best ways communities can combat pollution as part of his university research.

“I really advocate for making sure that the undeniable value of our aquatic ecosystems are reflected in our laws and the application and enforcement of those laws,” he says. “I think that’s the number one action that we can do or we can take.”

Voting for government representatives who support environmental conservation can lead to change on a larger scale. Venturelli also says that researching how local organizations dispose of their waste and ensuring they are following environmental laws is also an effective way to combat pollution.

“Just try to do small things that are accessible to you,” Emily says. “If we all start doing things like that, then that will really make a huge difference in the end.”

Sources: Coral Reef Alliance, United States Environmental Protection Agency, NOAA, NOAA, NOAA, Coral Restoration Foundation, Our World in Data, Reef Authority, NOAA Fisheries, NOAA, NOAA Satellite and Information Service