Corey Hagelberg uses art to call attention to the environmental problems he sees around him.

Corey Hagelberg loves connecting people with their environments and igniting conversations about the issues depicted in his art.

He is a social practice artist and co-founder of the Calumet Artist Residency, based in Miller Beach near the Indiana Dunes National Lakeshore. His art depicts environmental injustice, aiming to help audiences understand the impact humans have on the landscape.

Corey earned a master’s degree in printmaking from Ball State University in 2011, now specializing in woodcut. He focuses on the destruction of diverse ecosystems along the shoreline of Lake Michigan, combining his appreciation of nature with environmental advocacy.

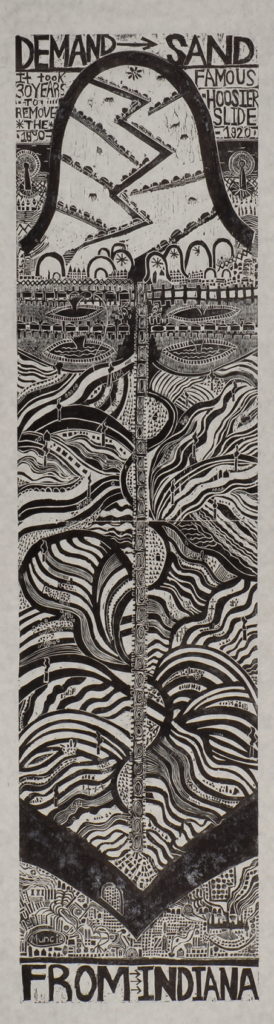

One of Corey’s woodcut prints, The Hoosier Slide, depicts a famous 200-foot sand dune that once sat in Michigan City, Indiana. Over a 30-year period beginning in the 1890s, the dune was dismantled and its sand hauled as far away as Mexico. In Muncie, the Ball Brothers used some of this sand to make their iconic blue-green canning jar. The logging of trees and removal of sand in the area destroyed a diverse habitat.

More than 13 million tons of sand were taken from the Hoosier Slide until it was no more. Afterward, a coal-fired energy plant was built on the site and has been in operation for decades. Corey’s woodcut print depicts the sand dune and the ecosystem that once thrived there. The image includes a zigzag path, showing carts hauling the sand away.

Corey considers himself a social practice artist, which means he aims to create art that calls attention to social issues such as pollution or climate change. He is an active member of Indiana Beyond Coal, a campaign to educate people about the cost of using coal as an energy source, and to push Indiana to invest in clean energy.

“I think of art as being embedded into all manners of life,” says Corey. He combines traditional art practice with community projects, and his projects are based on the special ecosystems of northwest Indiana.

Through the residency program, for example, Corey creates opportunities for artists to interact with the Gary community. The Calumet Artist Residency recently hosted playwright Jeff Biggers, and together, they created an original play called “Ecopolis.” The show, which featured local writers and performers, told the story of Gary as a regenerative and self-sustainable city.

Corey also worked with youth at local schools, churches, and libraries to paint a mural called Our Ecopolis. The mural consists of three canvas panels and depicts the community in a future beyond fossil fuels. The Steel City Academy is shown with solar panels, Ralph Waldo Emerson High School as a center of self-reliance, the Schahfer Generating Station as a bird sanctuary and job training center, and the Michigan City Generating Station (on the former site of the Hoosier Slide sand dune) with a green roof that feeds the community.

“More and more,” Corey says, “people inspire the work I’ve been making today.”

Drawing attention to problems through art isn’t new. For example, social realist art publicized the disparity of working-class people throughout the Great Depression. Lara Kuykendall, an associate professor of art history at Ball State, says social realism in America developed in response to the economic turmoil of the 1930s.

Examples of social realism include paintings by Ben Shahn and Philip Evergood, as well as Dust Bowl photographs such as Migrant Mother by Dorothea Lange. Each of these artists documented a form of human suffering or some other injustice in their work.

“If you can be savvy about interpreting a work of social realism,” Kuykendall says, “you can also come to learn how to consume contemporary news about war, economics, and politics.” For example, Evergood’s American Tragedy might help viewers today understand the nature of American labor unions and fair labor practices.

Although his art is not classified as social realism, Corey’s projects each have a very real message that people can learn from. His work goes beyond the art gallery and seeps into the community, setting the stage for dialogue about his region’s environmental concerns.