While a growing STEM industry demands more educators than ever, graduates often choose the higher salary of jobs in the field over working as teachers.

Ben Yoss expected college to be impossible. The 200-mile voyage to Rose-Hulman Institute from his hometown of Fort Wayne seemed especially daunting in the days before starting his freshman year last August, but he was excited to begin.

Now, a year separated from his first move-in day, Ben says classes at Rose-Hulman are less difficult than he’d expected. But math and science had never been foreign to Ben, who thrived in STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) subjects at Northrop High School.

Before graduating high school, Ben was able to take several classes through Purdue University Fort Wayne (formerly Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne) that counted for credit at his current college. Finishing math classes up through calculus during high school let him get a jump-start in college, making it seem a little less impossible.

Indiana mandates that each public school district in the state must offer Advanced Placement (AP) science and math courses that expand students’ knowledge and help them earn college credit. But Hoosier students often struggle to succeed in STEM subjects. In the four most commonly taken science and math AP exams in 2016, Indiana students averaged a score of 2.6, which is 0.4 points below a passing grade.

While STEM graduates flock to the workforce to make six-figure salaries, school districts are having a hard time finding teachers to help develop the next generation of STEM workers. Educators across Indiana and the rest of the country worry that quality STEM classes are not being offered in public schools, an issue experts have found is largely due to a lack of teachers.

In 2015, the Interim Study Committee on Education found that a significant shortage in STEM and dual-credit educators in Indiana had damaged the quality of STEM education. Over time, the wound has not healed. Indiana still had teacher shortages in all areas of science, math, and technology education for the 2017-2018 school year, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Help Wanted

Plenty of opportunities are available for STEM graduates who make it out of college. More than 8.5 million people in the U.S. held STEM-related jobs in 2015. This specialized workforce, which encompasses careers from agriculture and food science technicians to land surveyors, accounts for more than 6 percent of the U.S. workforce.

The average STEM employee makes $87,570 annually, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. That’s drastically higher than the general U.S. average income of $48,320, and 93 percent of all people in STEM occupations earn more than the national average.

STEM job growth nearly doubled over the first six years after the 2008 recession, and the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics predicts the field will grow another 6.5 percent by the end of 2024.

With general STEM jobs looking more fruitful, it’s getting harder to convince qualified grads to pursue a less lucrative career in education.

Francis Vigeant, CEO of a science curriculum provider called KnowAtom, says the low pay of teaching jobs compared to that of most other STEM careers is one of two major reasons for the nationwide shortage of qualified educators. The average starting salary for teachers in Indiana runs just over $35,000, according to the National Education Association. That’s less than half the average wage for STEM workers in the U.S.

If teachers earned at least enough money to fairly reward them for the effort they put into the job, Vigeant says schools would attract more teaching candidates and make current teachers happier.

Vigeant says STEM graduates tend to shy away from teaching for another reason: It’s hard. Teaching often demands more time than a specialized STEM job, and Vigeant says it can take more than 10 years at one school for a teacher to feel entirely comfortable in the role. By then, many teachers leave the profession.

Vigeant says it’s especially hard to employ qualified STEM teachers at the middle school level. In most cases, middle school students are first experiencing classes with specialized teachers for each subject. During this transition, teacher attitudes often shift to being more authoritative, discouraging a lot of students from that particular subject. Vigeant says many students, especially young girls, begin thinking they’re not good at science and math at this level and eliminate STEM careers as a future possibility.

Ben is thankful for his own experience in middle school, when a teacher encouraged him to be more enthusiastic about math. Ben believes he would not be as good at math as he is today if it wasn’t for that positive message from his teacher.

Changing the Standard

A 2016 report by the Learning Policy Institute determined that Indiana was an unattractive state for teachers based on wages, support, and other factors, ranking close to last in the country for teacher recruitment and retention.

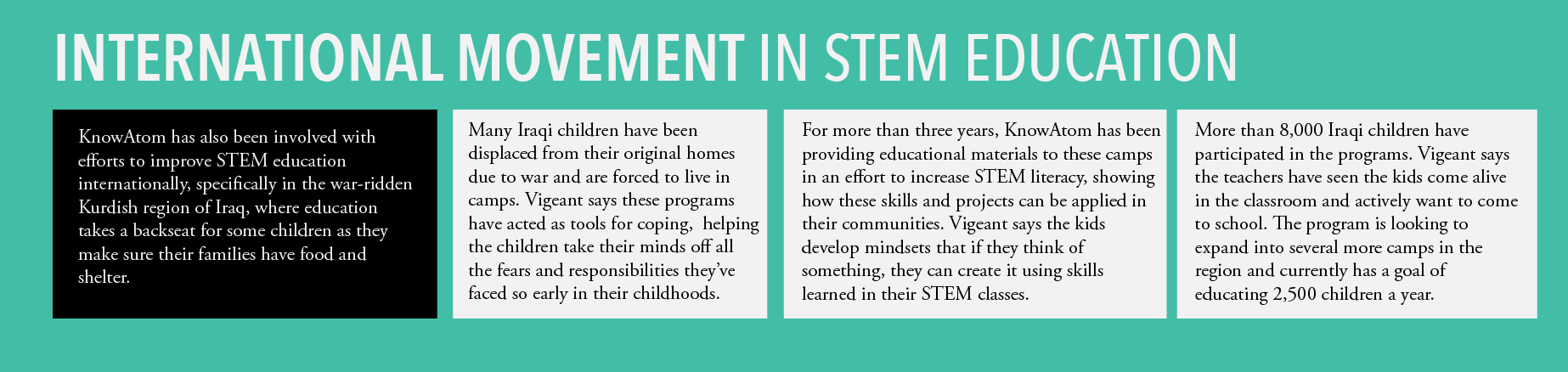

Vigeant started KnowAtom to provide educators, specifically STEM teachers, with the skills and tools they need to become more experienced. The company aims to improve the culture of education, challenge and develop student abilities, and help teachers adapt to the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS). Indiana hasn’t followed the 19 states who’ve fully adopted this curriculum as a replacement to Common Core, but the new state-centric standards do closely resemble those of NGSS.

Typical science classes focus on the history of scientific breakthroughs rather than what it takes to create breakthroughs of the future, Vigeant says. But NGSS puts students in the roles of scientists and engineers, helping them become better at solving STEM problems.

In a 2016 blog post, Vigeant explains the need for a new teaching model for STEM students at around the fifth-grade level. Students above the age of 10 learn better through application and independent problem solving than through recitation of facts, Vigeant writes. In his ideal classroom, real-life scenarios should drive teaching.

At one KnowAtom site visit, for example, a third-grade teacher told Vigeant about a solution to overpopulation a student had come up with. When learning about rock cycles and volcanoes, the student wondered if scientists could control volcanic eruptions to create new land masses for people to live on.

In high school, a teacher solidified Ben’s interest in chemistry by explaining concepts thoroughly and keeping a positive culture in a difficult course. This eventually led Ben to pursue a degree in chemical engineering, which utilizes both his mathematic and scientific skills.

While he could see himself teaching someday, Ben is currently undecided about his future career path. Either way, he hopes to start out in the STEM workforce after graduation so he can gain authentic, real-world experiences to share with potential students.