Natural hair has long been discriminated against. Now, a new natural hair movement is starting to take shape.

Nykasia Williams was 7 when the cycle began. Wash hair. Run the hair through the hot plates of the flat iron. Wait 2 to 3 weeks. Repeat.

Nykasia’s mom told her that the straight hair was more tamable, and it would look better for picture day. Her own hair was straightened through chemical relaxants, and she thought her daughter would like the sleek hair.

Nykasia’s mom and other older family members insulted the natural curl, favoring straight or relaxed styling. They said it looked smooth, and this support became a big source of confidence for her as a child.

While Nykasia never got it chemically relaxed, she did keep her hair straight most of the time. It was more manageable, after all.

Her mom’s voice was echoed by classmates. Nykasia attended Avon High School, which had a 69% white student population when Nykasia graduated in 2018. None of her peers wore natural hair like hers, so she didn’t have the confidence to show her curls.

During high school, Nykasia would sometimes try sew-in hair, a less coarse look that matched her white classmates. Sew-ins received the most compliments, especially the straight bob with purple ends Nykasia wore for a season. It wasn’t much like her natural hair, but she did like the unique look.

“Starting my natural hair journey, I was so worried about what people would think about me, so it hindered me from starting my journey at an earlier age,” Nykasia says.

Her high school’s culture suppressed Nykasia’s desire to liberate her natural curls; however, college introduced her to a group of women that helped free her hair.

Soon after arriving at Ball State University, Nykasia joined a club called Pinky Promise. The club seeks to provide sisterhood for Christian women and it’s where Nykasia found a lot of close friends.

Black women account for most of the members of Pinky Promise at Ball State. Nykasia noticed a lot of them wearing their natural curls, something she wasn’t used to seeing as a child. She desired that freedom.

So Nykasia called her cousin, Daja Gilbert. She asked if she’d like to transition to natural hair together.

Two and a half years ago, Nykasia got her hair cut short to start her natural hair journey.

Nykasia says to start growing the curls, most women do a “big chop.” They cut off all their damaged hair, sometimes getting their hair trimmed into a fade.

It’s a cathartic moment of sorts. The dry ends get snipped to the ground alongside the expectation of smooth, flat hair.

Nykasia’s ends were so fried they were always straight, contrasting with her coily roots. She knew it would take time to get her hair to match from her roots to the tips. That’s why she calls it a natural hair journey.

Her aunts and grandma were not supportive of Nykasia and Daja at first. They’d say things like, “What are you doing with your hair?” or “Is that how you’re going to do your hair today?”

“It was very discouraging because it’s so hard not to give in to their critique,” Nykasia says. She was constantly tempted to straighten her hair to avoid the critique and maintenance. But she knew she wanted to improve her texture.

Nykasia and Daja stayed motivated. They sent each other selfies with the bouncier curls and researched products, exchanging advice.

It wasn’t easy to find products for their hair. Nykasia estimates that only 5% to 10% of the products at Walmart in Muncie are made for black women. She felt like she was wasting money as she gave products a try.

She says it’s getting better, especially at Target. But it’s more expensive. And after a while, the product loses its effect. Then it’s back to the aisles to hunt for 4c-friendly hair care.

Alexis McGill Johnson, executive director of the Perception Institute, also struggled in the shampoo aisle. She knew there was a stigma against black women’s natural hair, so she proposed the “Good Hair” study.

“All these experiences [Johnson] was having and other women were having, we didn’t have the hard numbers for,” Jessica MacFarlane, research associate for Perception Institute, says. “We wanted to lend some data to the conversation.”

Perception Institute’s “Good Hair” study shows that black women carry more anxiety over their hair than white women. This discomfort manifests as many black women choosing to forgo their coils and curls for relaxed hair or sew-in hair.

Now, there’s a new generation of self-proclaimed “naturalistas,” or people who support natural hair of all types. The same study showed millennial naturalistas were the most supportive of textured hair.

Older generations are accustomed to a stigma against kinky hair, as it’s been a source of tension throughout United States history. As Europeans dehumanized slaves, they’d shave their heads to symbolize the loss of their culture.

In 1981, Renee Rogers sued American Airlines when the company made her take out her cornrows to work as an airport operations agent. The case ended in the airline’s favor, stating that braids are not a characteristic of race.

Braids are an essential for Nykasia. She says they help her grow her hair out and have less daily maintenance.

“My hair is my expression of freedom because it is very versatile. It’s easy to change my hairstyle based on my feeling for the day,” Nykasia says. “It’s very liberating and helps me express who I am.”

In May of 2018, Brittany Noble Jones was fired from her job as a newscaster for wearing her hair natural. The station called her hair “unprofessional.”

One-fifth of black women feel social pressure to straighten their hair for work, which is double the portion of white women who feel that pressure, according to the “Good Hair” study.

In July, California and New York signed legislation to ban racial-based hair discrimination. This legislation has also been proposed in Illinois, Kentucky, Michigan, New Jersey, Tennessee, and Wisconsin.

Black women are starting to get the legal protection to wear their natural curls, but it takes personal confidence to put the straightener down.

MacFarlane says a lot of black women have responded to the “Good Hair” study, thanking the researchers for the study. It affirmed their experience.

“I don’t have that emotional and financial burden because society is not telling me I need to change my hair,” MacFarlane says.

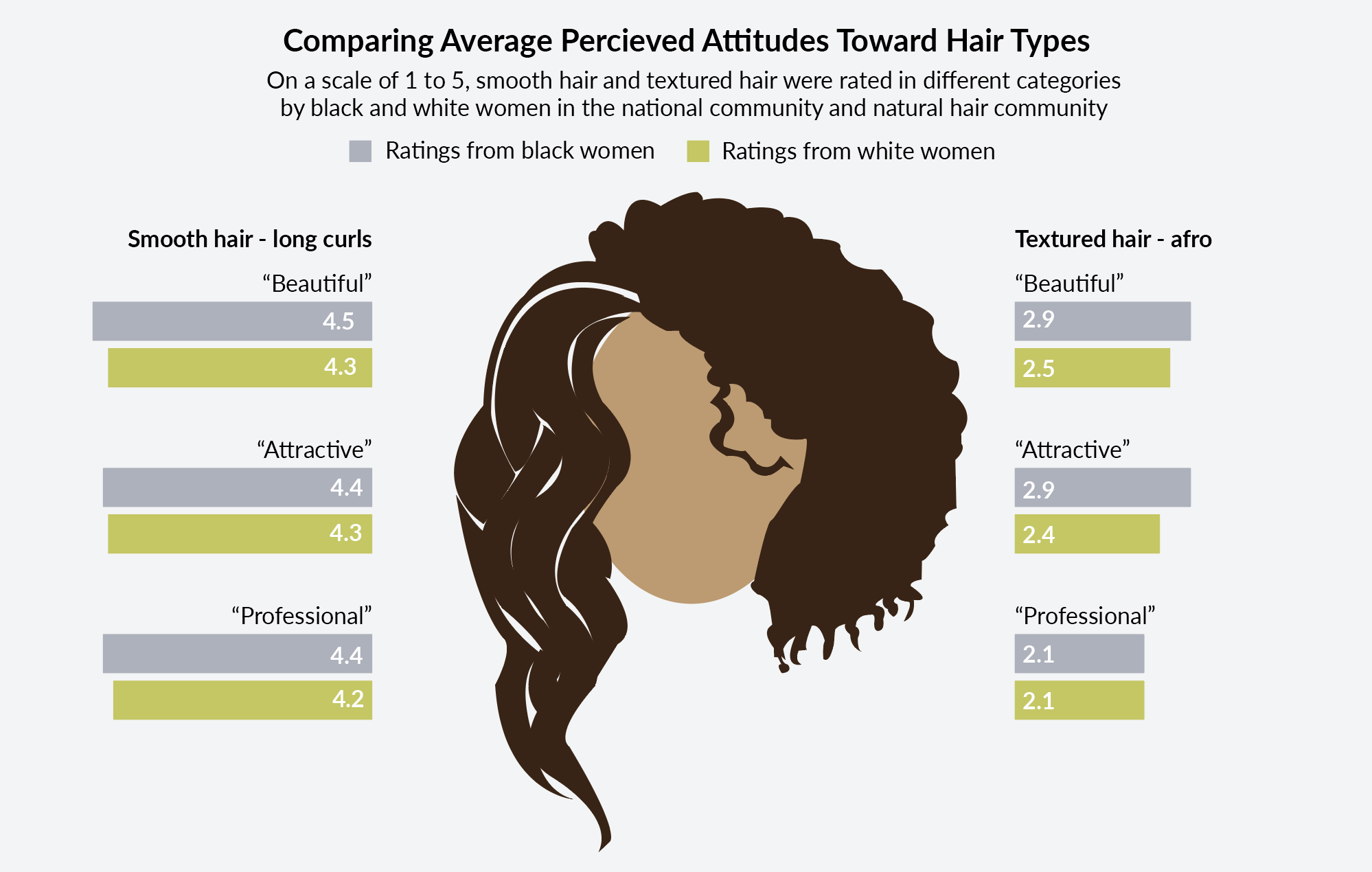

Part of the “Good Hair” study is an implicit bias test, where subjects’ true thoughts are shown in their ability to match natural hair to adjectives like “beautiful” or “messy.” Participants are told to quickly match textured hair to positive adjectives and smooth hair to negative adjectives and then told to do the reverse. Quick association with positive terms shows favored opinions.

Only 3% of white women in the “Good Hair” study tested strongly in favor of textured hair, in comparison to 13% of black women.

Those that belong to the natural hair community were more likely to favor textured hair. One-third of black women who identify as naturalistas scored pro-texture. Many of these women are millennials, showing there may be a generational shift in the way natural hair is perceived.

Usually, people are hesitant to share their biases explicitly, MacFarlane says. But when judging black women’s hair, people— especially white women— were comfortable sharing negative perspectives.

The study also asked women to rate afros on a five-point scale. Both black and white participants gave the hairstyle low marks, especially in professionalism. Long, loose curls were rated much higher.

Activist Angela Davis donned an afro to rebel against white beauty standards during the “Black is Beautiful” movement in the 60s. It became a symbol of black power and holds sentiment today.

Nykasia thinks the idea of textures being professional is ignorant. Afros are just as professional as any other style, she says.

Nykasia says “professional” loose curls aren’t really possible with her hair. She has 4c hair texture, which means her curls are tight and voluminous and can easily form an afro. This is the curliest of the 10 hair textures.

When her high school show choir director instructed the women in the choir to wear loose curls, Nykasia had to buy a sew-in weave. The hair treatment costs around $275.

Nykasia wishes she would’ve said something to the director. She was one of only two women of color in the group and wanted to be obedient. But it wasn’t fair.

It’s easy to get bogged down by all the roadblocks to natural locks. But sharing her journey helps relieve the frustration. Nykasia tries to post pictures on her good hair days and shared about her hair during her internship at the Indiana Writers Center.

Nykasia was challenged to share with elementary and middle school students a time she faced adversity because of appearance. She was hesitant to share the anxieties she faced when transitioning to natural hair.

“My intention was to not only let the students know that their natural hair is beautiful, but to also remind them that their story matters,” Nykasia wrote in a blog post during her internship.

Nykasia’s glad she got a little bold with the students because one girl enthusiastically echoed her complaints. Nykasia hopes the girl will have the confidence that she lacked at that age to defy the standards set by others.

The flat iron has been handed down from generation to generation. But naturalistas like Nykasia are starting to push toward the appreciation of finer curls.