It was 1990. Tracy Cochrane, who was only 16 years old, was charged with first-degree murder. Two years later, he was sentenced to 67 years in prison in Illinois. He never thought he’d see the “real world” again.

Tracy lived his life day by day, especially since he wouldn’t get out until he was in his 80s — if he lived that long. So when laws quickly changed and Tracy was released immediately, he didn’t know how to deal with it.

When he went to prison in Illinois, the only cell phones that existed were brick phones, and Google was a figment of imagination. There were a few options to help prisoners with reentry, but with an immediate release and COVID-19 going strong, Tracy was released after 30 years in prison with little help to adapt to the world again.

“What prison doesn’t do is they never prepare you for the emotional toll it takes on you once you get out,” Tracy says.

The reality of re-entry

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics, approximately 95% of State prisoners will be released at some point.

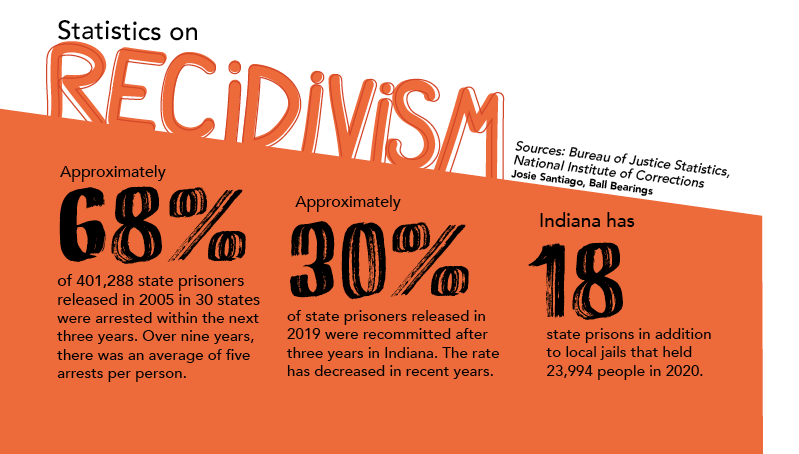

Despite this, there is a lack of programs to help returning citizens, or people who were previously incarcerated, and it’s a reason the recidivism rate in the United States is so high.

Recidivism, according to the Indiana Department of Correction, is a return to incarceration within three years of an offender’s date of release from a correctional institution.

Jennifer Schriver, a professor and the chairperson of the Department of Psychology at Indiana State University, has been doing research to help with issues for people who are incarcerated and with reentry.

Reentry, according to the National Institute of Justice, is the transition from life in jail or prison to life in the community.

Returning citizens need to consider a number of things once they’re released from prison: housing, medical care, employment, getting a drivers’ license, insurance, mental health treatment, and more.

“The longer you spend inside, the fewer connections you have outside, the fewer resources you have on your release,” Schriver says.

She says the title of being a felon adds to this because, depending on the crime, that label can restrict people from public housing, voting, where they can live, what jobs they can have, etc.

Misconceptions can make life for returning citizens more difficult. Schriver says many people have the misconception that everyone who is incarcerated is dangerous or violent, but most people in prison are there for nonviolent charges.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, approximately 72% of federal prisoners are serving time for non-violent offenses and have no history

of violence.

One of the biggest struggles Schriver has seen after returning citizens leave prison is being overwhelmed by the amount of freedom they have and adapting to having choices again.

Lost time

This is something Tracy noticed once he was released from prison. Since he was conditioned to a life

without any freedoms, it was hard for him to adapt.

He mentioned relating to a fellow inmate who broke down at the supermarket because the number of options was too much. The amount of pressure Tracy felt after coming home led him to have a mental breakdown in his room.

“You realize that you’re out, and you have all these emotions coming to you that you had locked away for so long and don’t know how to deal with,” Tracy says.

He was 16 when he turned himself in to the police. He stayed in youth detention centers until he was 18, and then he was convicted of first-degree murder as an adult and sent to prison.

Tracy took a plea agreement of 67 years, but he says he felt coerced to take it.

On March 31, 1990, along with a friend, Tracy abetted in the murder of his father.

According to case details from People vs. Cochrane, Tracy and his friend murdered his father to stop him from calling the police about a burglary they’d committed at his home.

Tracy says he wanted to go to trial to present the mitigating facts.

He says his dad was an “abusive alcoholic” who molested a young family member growing up.

Tracy says his lawyer told him he would be found guilty regardless and encouraged him to take the plea rather than risk getting natural life.

Tracy stayed in three prisons in Illinois during his 30 years: Old Joliet Prison, Menard Correctional Facility, and Danville Correctional Center, where he was eventually released.

When Tracy started his life in a correctional facility, he tried to stay in contact with his friends and family, but he realized quickly how difficult it would be. Other people had lives to live or struggled to see him. In the beginning, he tried to keep up with the outside world.

“I got in my head like, ‘You’re never going to get out of prison, so why pay attention to anything that is going on [outside of prison] because that’s just keeping dreams and hopes alive that you shouldn’t have,’” Tracy says.

He tried to stay busy in prison by studying religion and working. Tracy also took carpentry classes, but since the only education he had was from a book, he doesn’t feel confident putting what he learned into action.

Unlike other prisoners, Tracy didn’t realize he was going to get out of prison when he did. Illinois Public Act 100-1182 was passed in 2020, making it unconstitutional for any juvenile 17 years old or younger to be given a life sentence without parole.

Because of this, anyone who was eligible but had been convicted between 1978 and 2019 were released under certain circumstances. For those convicted of first-degree murder, it was 20 years or more, and since Tracy had already served 30, he was released immediately.

Tracy had heard about the law, so he tried to prepare himself for potential release, but with it being 2020, there wasn’t much he could do.

“You can’t be a burden to anyone,” Tracy says to himself. “You’ve already been a burden the whole time you were in prison, so you can’t do that once you get out.”

On the day Tracy was released, he was overwhelmed. His family picked him up, but they weren’t sure where to take him. He was planning to stay with his brother, but according to Illinois 720 ILCS 5/12-36, felons aren’t allowed to live with “vicious dogs,” including German shepherds and pitbulls. His brother had both, so he wasn’t able to stay there until another relative took the dogs.

When he walked in, his younger brother was sitting on the couch, and he had grown nephews there he’d never met.

“When you’re in there, everything stops, and then you get out and realize how fast life goes on,” Tracy says.

Once the Illinois native was released, he was shocked by the lack of people outdoors because of COVID-19. He felt like he had gone from a big prison to an even smaller one.

He says in prison he was “brainwashed” to think no one would give him a job because he was a felon. Having to use the Internet to apply for jobs was another struggle for him. Eventually, he got

frustrated, walked into a place, and was offered a job.

Since then, Tracy has become a “Christ follower” and has been able to keep some of the relationships with other men he met in prison.

“We’ll talk about how you don’t miss prison, but you miss all the people you met in prison, and some people were actually good people who made mistakes in their lives and are trying to correct those mistakes,” he says. “Not everyone in there is a terrible person.”

Today, Tracy works in a factory that produces hygienic products for hospitals and prisons.

“My worst day out here is better than my best day in prison,” he says.

Despite this, Tracy doesn’t want to forget about his time in prison because it made him who he is today, and he is proud of himself.

Appreciating the little things

The first thing Josh DeVore did after spending almost 10 years at Danville Correctional Center was get a bacon cheeseburger.

“Prison food is almost like school food,” he says. “It’s a little worse than that though, it’s very bland, there is no seasoning.”

Josh served nine years after being convicted in 2012 for possession of cocaine with intent to deliver. He was sentenced to 14 years in Illinois, but he got out early on good time and was released in 2021.

Josh was able to make good time by working in the prison’s recycling plant and taking a handful of college courses. He was close to getting his associate’s degree when COVID-19 hit.

He tried to have routines and stay busy during his time in prison. He made a couple phone calls home a week, but he tried not to worry too much about the outside world.

“You miss a lot of things out there,” he says. “I have two nephews now. When I went in, I had one, and he was 5,” he says. “[My sister] had another kid when I was gone, and I didn’t even meet him until I came home, so he was already 7 years old.”

During his time at Danville, Josh’s grandfather, who he was close with, passed away. In some circumstances, prisoners can pay to have guards transport them to a funeral or memorial service to say goodbye to their loved ones. Since his grandfather wasn’t his immediate family, Josh wasn’t allowed to attend.

He became both nervous and excited as his release date grew closer.

Once COVID-19 hit, he was able to get three extra months of good time because the prison wanted to get people out who were close to their release date. There had been a class to prepare returning citizens for reentry, but the virus shut it down.

“You don’t really know what to expect coming

home,” he says. “You talk to everybody, but at the same time, you’re pretty much completely

starting over.”

On the morning of his release, he was given a state-issued ID and was allowed to take home or donate any of his belongings. Then, he was given donated clothing to wear out and any money left in his account from the work he’d done.

His parents and his sister picked him up from the correctional facility on Super Bowl weekend. It was a surreal experience for him to come back to a Super Bowl party.

“Everything seemed like it was moving at 100 miles per hour,” he says. “That first week I was home, I really just wanted to go in my room and shut my door and hide for a minute.”

It took Josh about two to three months before he was able to get life figured out again. He passed his driver’s license test on his first try and started a small business with his father doing stump and tree removals.

Despite having had a cell phone before he went to prison, technology was still quite a shock to him

once released.

“My 7-year-old nephew … he was setting up stuff on my phone for me that I don’t even know how to do,” he says.

Josh says they’d just brought iPads into prison before he left, and for most of his time there, they were still using cassettes and tape players.

Josh looks back on his time knowing it all happened for a reason.

“Some parts of that probably made me a better person,” he says. “I’m away from all the bullshit. I don’t even think about that other part of my life anymore.”

Josh is in a good place. He has a girlfriend, and they just had a baby in January. When he went into prison, he was 31, so he thought his life was over, that he was too old to have kids, but now he sees that he still has plenty of time.

Life in prison has made him have more appreciation for the little things in life.

“Taking a shower without having to have shower shoes on, eating whatever you want to at any time — those are the things that I missed when I was in the joint that I didn’t realize I had before I left,” he says.

A second chance

Despite being in jail for a similar amount of time, Alex Crossen’s reentry experience was much different than Josh’s. Alex was in prison from March 13, 2011 to Dec. 4, 2023, but instead of being immediately released, he spent the final year of his term at a work release center.

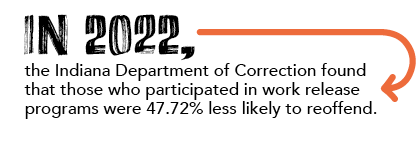

At work release centers, prisoners are able to get experience working outside of prison and preparing for life after their release.

“I really feel like this is a really positive and good opportunity for most people that come out because of the structure that it gives,” Alex says.

When Alex went to prison, he was 21: the same amount of years he was originally sentenced to. Alex was convicted of aggravated kidnapping of an adult.

He was looking to fit in and started to hang out with a crowd who, he says, didn’t make “the best decisions.” While he was with them, someone robbed him and another friend, so they decided to confront the man. This is when the crime

was committed.

Despite having the gut-wrenching sinking feeling about the decision, Alex turned himself in.

Once he went to prison, he tried to take initiative and figure out what he wanted to gain from his time there. He did this by getting in tune mentally

with himself.

“The stay is not anything that anyone would want. It automatically strips you of any say so for yourself,” Alex says. “You get told what to do in every aspect of your life moving forward. The stay is never something that’s comfortable, that’s easy, but I made the most out of it.”

While at correctional facilities, he started college courses, and he ended up working his way up into a role where he helped place other individuals throughout the facility.

According to the Department of Justice, the more programs offenders are involved in, whether that be work or educational courses, the less likely they are to return to prison.

Alex says one of the biggest hardships about being in prison is that it hurts your loved ones. He spent time at Pinckneyville Correctional Center and Danville Correctional Center, so his visitors had to drive over six hours to visit him. Due to the amount of effort it took for people to visit him, he lost a lot of people in his life.

One challenge Alex struggled with after being released was setting up health care and finding a primary physician. He believes people not having enough preparation for leaving prison is why recidivism is so high.

During his time at the work release center, Alex worked and was required to save money, so each week, they’d take his check and give him an allowance. This was so he would have money saved up for housing, transportation, and food once finished with the work release.

Since leaving prison, Alex has learned to think twice before he reacts and make decisions for himself. He doesn’t let small pressures like work or car troubles get to him.

“I’m just being appreciative, being grateful for what one would call a second chance,” he says.

Over 650,000 people from State and Federal prisons, according to the White House, will become returning citizens every year.

As of 2024, President Joe Biden proclaimed April as Second Chance Month. Biden says Second Chance Month is an opportunity to support returning citizens and give them a fair shot at “the American Dream.”

Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics, Indiana Department of Correction, National Institute of Justice, Prison Policy Initiative, casetext, USLegal, ILGA, Find Law, U.S. Department of Justice, Indiana Department of Correction, Department of Justice, The White House