It’s 1954. The shops in The Village are booming after World War II, with a mini shopping mall and a high-end shoe store moving to the strip. The College Sweet Shop is the hangout spot for college kids, and The Village is all funded by Riverside Neighborhood.

Ball State University grows. Students and renters move into the area. McGalliard’s business increases. Muncie’s industry begins to die, and soon enough, The Village and downtown Muncie die with it.

After years and years of trying, Ball State and Muncie have hatched a plan to try to rebuild the famous strip on West University Avenue. With the addition of a theatre, a hotel, and a mix of housing and commercial sites, the city is committed to improve the area’s economy, but what does that mean for the businesses already there?

Is this gentrification or revitalization? This is the question that was asked early on in the research stages of the plan for The Village’s future. As a studier of Muncie, Jennifer Erickson, professor of anthropology, doesn’t know, but she’s looking to find out.

What is gentrification

In simple terms, according to the Urban Displacement Project, gentrification is a process where there is an economic change in a historically disinvested neighborhood. This change often comes when a wealthier group of people move into predominantly lower-income neighborhoods.

It is a complex process that typically makes economic investment in the neighborhood increase, causing the rent and property value in those neighborhoods to increase as well.

According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), in terms of gentrification and racial displacement, it’s often white home buyers coming and displacing the minority residents who lived there before.

Associate professor of architecture Tom Collins has lived in Muncie for the past eight years. He lives in downtown Muncie, and through his architectural work, he has seen gentrification firsthand.

“At a surface level, [gentrification] might seem like a good thing because depressed neighborhoods have a lot of blight,” Tom says. “But unfortunately, what it also means is that as the property values rise, the folks that originally lived there no longer can afford to live there anymore, and they’re displaced.”

While there are a number of positives that can come with the process, including new people in the community; investment in the area; and improvement of the economy, the high taxes, and rent means long-term residents cannot afford to live there anymore.

The urbanization of gentrification

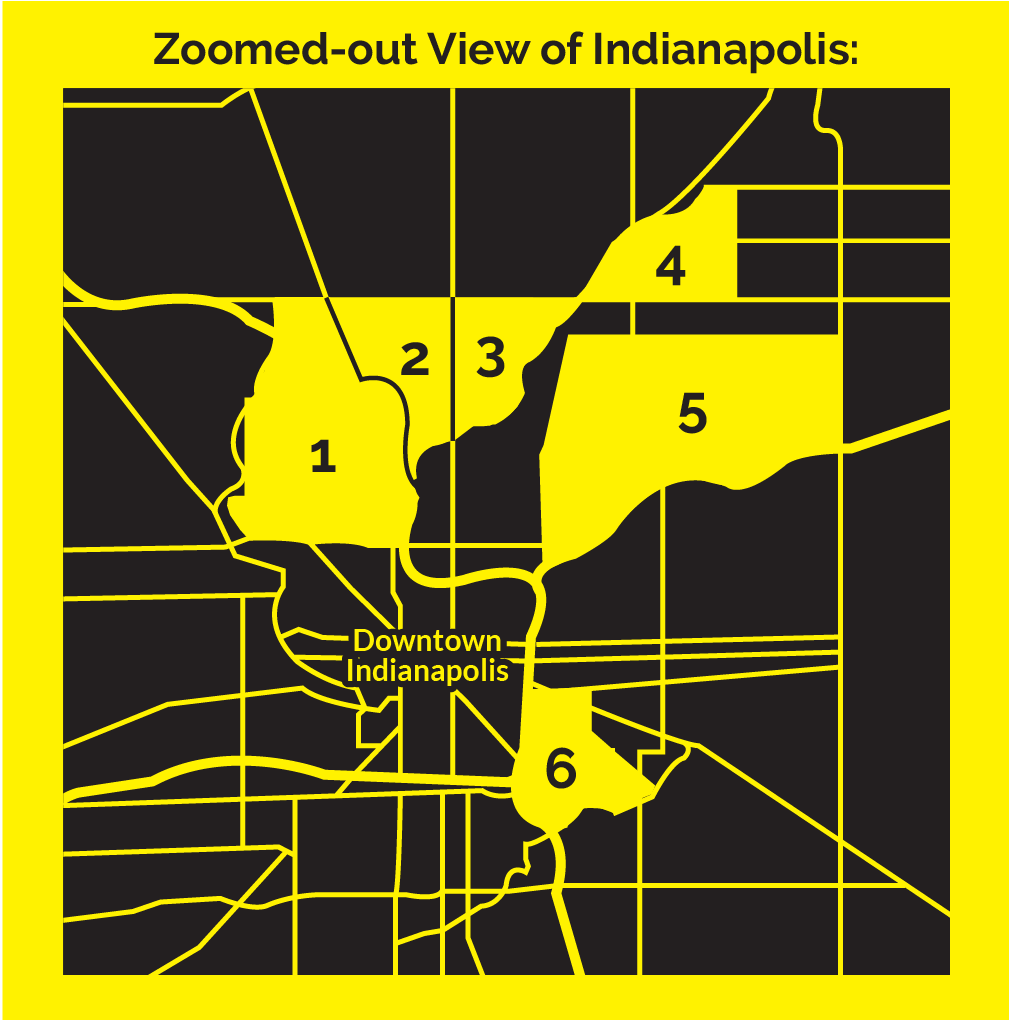

Gentrification is most common in big cities. In a study done by the NCRC in 2020, Indianapolis was number nine on the list of cities with the most gentrification.

Tom has done work in Indianapolis recently, and says he has seen much more gentrification there than in Muncie, not that it does not exist there too.

“People start to realize that maybe they want to live in the city or closer to the center of the city or they want a more urban lifestyle,” Tom says, “and they start buying up vacant parcels in these neighborhoods or they buy up old homes that are blighted or abandoned.”

It is most clear to Tom on the eastside of Indianapolis and in Fountain Square, a neighborhood that used to be “rough around the edges” but has transformed in the last few years. According to a report from SAVI, household income in Fountain Square increased by 47% from 2010 to 2016.

One argument against gentrification is that when a homogenous group of people move in, it eliminates the diversity and the culture of the neighborhood.

“It’s also about changing the things that make that particular neighborhood special or unique,” Tom says. “This is really where people who are very opposed to gentrification will say, ‘Look at that neighborhood, it used to be eclectic and quirky and fun … and all these little attributes that gave it its flair, and now look, 10 years later, it’s not like that anymore because all of the people that made it like that aren’t there anymore.’”

The history of Muncie

With only 60 miles between Indianapolis and Muncie, one might think gentrification would be in Muncie too. Some of it can be seen in small doses, for example, when it comes to The Village and certain areas of downtown.

But for the most part, gentrification is not an issue in Muncie, and the reason for that is due to a lack of demand for housing.

J.P. Hall, associate professor of historic preservation, served a term on the planning commission for Muncie and as regional director of east central Indiana for Indiana Landmarks. Therefore, he has been studying Muncie and its history for years.

Muncie is a post-industrial city. Hall says it boomed until the 1970s but has “steadily shrunk” ever since. Similarly to Detroit, South Bend, Indiana, and Gary, Indiana, most of the industry left Muncie after World War II.

“You see it in space, and you also feel it,” Hall says. “If you drive around the city, certain neighborhoods, certain areas are going to impart a certain feeling, and there are going to be certain conditions that you’re going to see in the built environment depending on where you’re at.”

The lack of industry in Muncie caused a loss of jobs, abandonment, poverty, and loss of income. According to StatsIndiana, the population of Muncie in 1980, at the end of the boom, was 77,216 people. In 2020, the number decreased to 65,194 people.

As Muncie began to be revitalized, this went toward building up Ball State and IU Health Ball Memorial Hospital, along with other things on the west side of Muncie. The “higher end neighborhoods” as Hall calls them, like Yorktowne Breckinridge and Halteman, reside on the Northwest side of the city.

Where the industry and factories used to be on the east and south sides now sits an abundance of vacant and abandoned homes.

“We have more housing than we need,” Hall says. “Now, you might say, ‘Well, but that’s housing on the southside in a post-industrial neighborhood or that is working class housing that is not not up to my standard,’ but that is a different situation.”

While there is an excess of undesirable housing in Muncie, there isn’t enough affordable housing. Muncie mayor Dan Ridenour recognizes this issue, making affordable housing one of his main goals for 2023’s Annual Action Plan. At the beginning of the year, 93 single-family homes were scheduled to be built in Muncie.

Because of these problems and lack of options, gentrification isn’t as present in Muncie as other cities.

Redlining

The lack of gentrification doesn’t mean it may not come or that there are no other issues. Redlining is a big problem in Muncie, and gentrification often comes after it.

Redlining, according to the Urban Displacement Project, was the practice of categorizing neighborhoods as undesirable on Home Owners’ Loan Corporation maps because they were deemed the riskiest in terms of loan issuance. These “hazardous” neighborhoods were predominantly ones of color. According to Federal Reserve History, redlining was outlawed in the 1868 Fair Housing Act because it was racially motivated.

“There is a lot of bias when upper-middle class folks buy homes in old neighborhoods,” Tom says. “They tend to see poor, disenfranchised populations in these neighborhoods as a problem, like we need to get rid of them, and that’s gentrification.”

Tom believes a part of the divide, or redlining, in Muncie is attributed to people not being comfortable with people different from them living so close.

With a shortage of 7.3 million affordable houses, according to Urban Institute, the United States is in an affordable housing crisis. Affordable housing, according to Anchor Group Solutions, is housing that costs less than 30% of a household’s gross monthly income.

In Tom’s experience with affordable housing, he has attended meetings to revitalize neighborhoods, including ones in Muncie, and he says even people in affordable housing often don’t want affordable houses to be built in their neighborhoods.

“People use affordable housing as a shorthand way of talking about poverty, and people have these assumptions about who poor people are,” he says. “You start hearing people saying, ‘I don’t want affordable housing’ because it’s not socially acceptable to say I don’t want poor people, … but they didn’t recognize that they’re one of them.”

Instead, some people like the idea of gentrification since it means property value goes up and they can try to sell their homes, but as families are pushed out because of gentrification, they often get into destabilizing patterns of moving from house to house.

“The real estate markets are so hot that there isn’t sufficient time for folks to respond to these gentrification pressures,” Tom says. “In Muncie, because that doesn’t happen, I feel we have this opportunity if we can recognize it’s a problem, … we can start to address it before it happens.”

Revitalization

There are plans in the works to turn things around in Muncie and get ahead of these issues.

Along with the plan for The Village, there is the TogetherDM plan, which Hall is a big supporter of. The long-range proposal discusses how downtown, the center of the city, should be the epicenter of revitalization, turning things around in a spot that is “neutral territory” between the divided sides of Muncie. This comprehensive plan was created from community input and professional planning.

“We have to … build housing down there very strategically and intensely in order to kind of reverse all that action that happened after World War II and to kind of recenter things because things have gotten off center here in Muncie,” he says.

Erickson, associate director of the Center for Middletown Studies, thinks revitalization in Muncie could be good or bad: pushing people out or boosting business. She can’t predict what will happen, but she hopes this restoration will include places that people who don’t have a lot of money can enjoy.

“If you’re going to revitalize an area, to use that term revitalization instead of gentrification, you are going to try to involve the community as much as possible,” she says. “You will be thinking about who is at this table and who’s not at this table.”