Boundaries created almost 85 years ago still haunt Muncie’s urban neighborhoods.

In the 1930s, U.S. citizens were in a panic. Home values were decreasing, inflation was out of control, and the American economy was in shambles.

According to the Harvard Business Review, house prices dropped about 67 percent between 1929 and 1932. This means that in 1932, a home that cost about $76,000 just three years earlier would be worth a measly $46,000.

As home values dropped, the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) was created with the purpose of saving lenders by increasing confidence and stabilizing prices. HOLC advised them which areas were “desirable” and safe for mortgages.

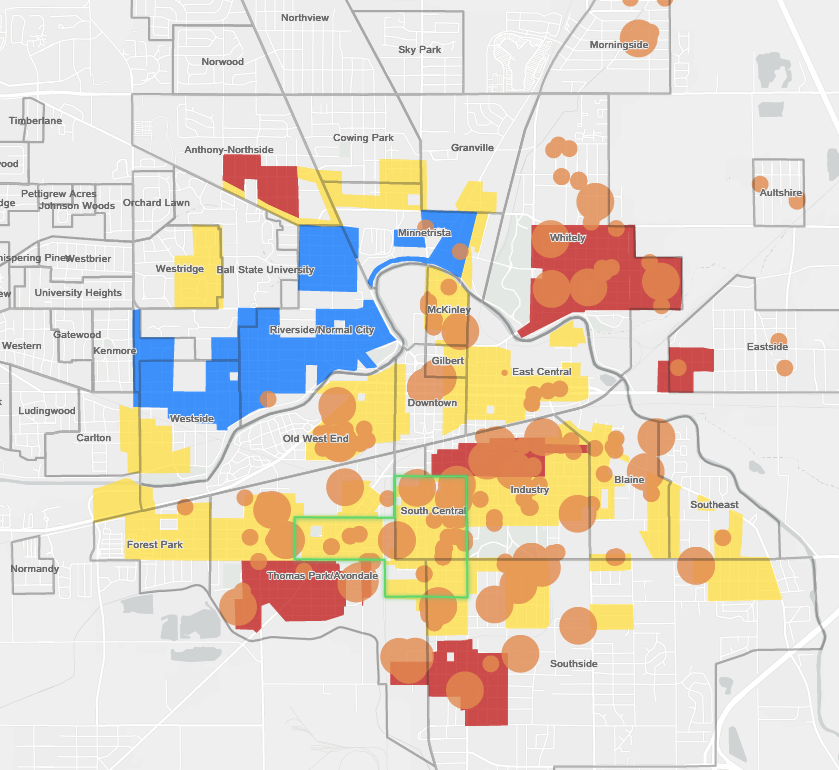

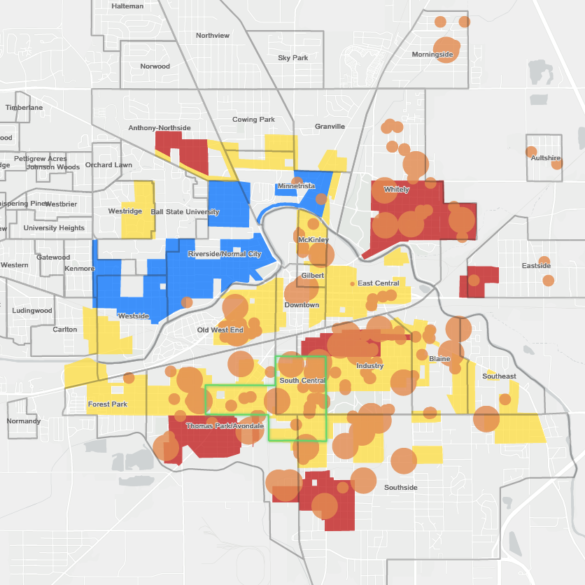

Regions of selected cities were classified into four categories — A, B, C, and D. According to the National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), factors that influenced the classifications included the general condition of housing in the area, proximity to amenities like parks, the economic class of residents, nationality, and ethnic/racial composition.

Areas with immigrants or people of color were frequently labeled C and D which were named “definitely declining” and “hazardous,” respectively. These determined sections were outlined on maps of 150 cities in yellow and red, separated from richer, and mostly white, neighborhoods.

Redlining, the practice of appraising areas as “hazardous,” has had negative effects on the areas it has been applied to. But redlining isn’t the only harmful classification — yellow areas, classified as “definitely declining,” have suffered similar consequences. This classification is known as yellowlining.

Although legislation like the Fair Housing Act of 1968, which prohibited discrimination concerning housing based on factors like race, religion, and sex, work to combat issues like redlining and yellowlining, the effects of these practices still linger.

Jena Ashby is the director of impact and programs at Muncie Habitat for Humanity, where she leads a team called the 8twelve Coalition. Their focus area includes the South Central and Thomas Park/Avondale neighborhoods, both of which were once classified as yellow.

One of the effects of redlining and yellowlining is a decrease in available mortgages.

“We know that our neighborhoods, which have historically been neighborhoods of color and even probably more southside-focused neighborhoods, do tend to have lower home ownership rates and less equity available to people to just fix their homes up,” Ashby says.

One of 8twelve’s goals is to ensure residents have access to decent, safe, stable, and affordable housing. While there are many ways to accomplish this, they’re often dealing with existing construction.

Ashby says the 8twelve Coalition and their partners have improved 160 properties in some way. That could be anything from repairing a house, building a small “pocket park,” or creating a rental property. All of this contributes to improving lives for people in the community.

“We want people to live in homes where they experience safety and affordability,” Ashby says. “When you can answer that question of, ‘Where do I live?’ then there are so many other things you get to pay attention to in life.”

Affordability is another challenge for organizations like 8twelve that focus on community revitalization. If not managed correctly, the prices of housing can inflate and push residents out of the neighborhood, also known as gentrification. Ashby says that Muncie has been fortunate that they haven’t experienced a lot of this phenomenon.

Another factor that can negatively affect safety and affordability in urban areas are blighted properties, or properties that are abandoned or unproductive. These properties are sometimes a result of the HOLC maps, and are generally reflective of the lack of investment in urban areas.

Blighted properties decrease the value of neighboring houses, and can create opportunities for illegal activities. Muncie has an estimated 2400 vacant lots, 1300 vacant structures, and 750 blighted structures which costs the City of Muncie $2.3 million in tax revenue.

Zane Bishop is the former Blight Elimination Program coordinator for the City of Muncie. Through this program, Bishop reports that Muncie has demolished 249 residential properties.

But demolition isn’t always the answer. Even when homes are demolished, the properties can become problematic.

“Sometimes nothing gets done with the vacant lots, and they just sit there. The grass gets tall. It attracts trash, debris, dumping, and parked cars,” Bishop says.

That’s where community revitalization organizations like 8twelve come in.

“We are kind of the point of entry and acquisition for property, and then we are able to hold on to that property until an end user can take title to it,” Ashby says.

Those “end users” can then develop the lots into productive properties that add value to the community. At the end of the day, Ashby says their focus is on improving the lives of people who live in their target area.

“I think there’s such a great spirit of collaboration, where I feel like we want everybody to win. So whatever I have that I can bring that helps you win, I want to do that. And I think our partners, especially in the coalition, have the same thing,” she says.

Ultimately, housing is just a portion of the work Ashby does at 8twelve. Their larger purpose is making people feel at home in their area.

“We’re always looking at that sense of community,” Ashby says. “We want people to feel connected to the place that they live, but also connected to the people that live near them as well.”

Although redlining and yellowlining have had a lasting effect on the Muncie community, work being done by organizations like 8twelve allow room for these labels to be erased.

Sources: Harvard Business Review, National Community Reinvestment Coalition (NCRC), NCRC, U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 8twelve Coalition, 8twelve Coalition

Featured Image: Alex Bracken