What it’s like living with an eating disorder

Content Warning: This story discusses detailed images, statistics, and actions related to eating disorders that may be triggering to some. Please read with caution.

I’d like to introduce you to Eda.

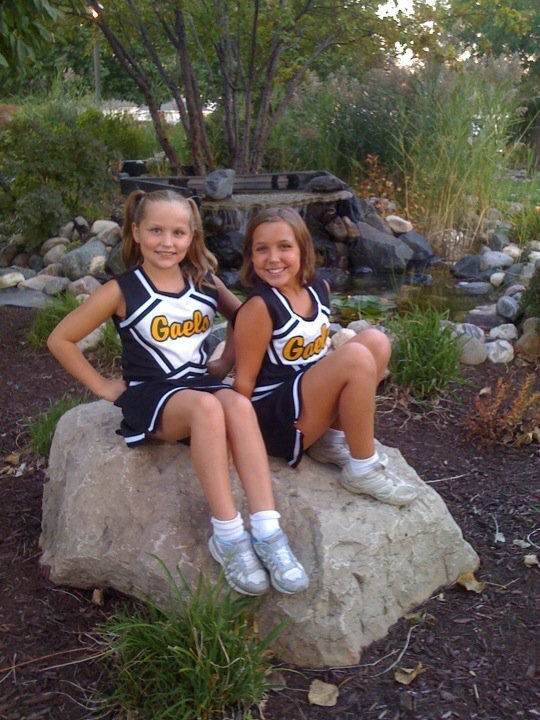

You could say Eda is a close friend of mine. We became best friends in first grade. We took ballet together. She always slept over and ate my favorite snacks with me — or didn’t.

Eda could be mean. She liked to remind me of how many times the straps of my skirt wrapped around my waist before being tied into a bow compared to the other girls’ waists in our ballet class. She encouraged me to make myself smaller, thinner, to have legs like theirs and a tummy that didn’t fold over my tutu.

She compared my measurements to the measurements of other girls in my dance class — mine were always bigger, too big for my ballet instructor to have dancing front and center stage at her dance recital in June. No one wants to see thighs touching at the end of a plié.

Eda’s favorite thing to do when we were little was watch Barbie movies and play with Bratz dolls and convince me that, when I grew up, I had to look just like them: tiny waists, toned legs and a gap as wide as my stack of “Judy Moody” chapter books between my thighs.

Since those movie nights, Eda has followed me everywhere — to the Bearcat Den, where myself and the other girls in middle school would change into our gym uniforms in front of one another. I was picked last by every team captain because no one thought I was fast enough or fit enough to be a good addition to their team. Eda told me they were right.

Eda followed me to the cafeteria, where half of my peanut butter and jelly sandwich would end up coming back home with me in my favorite Crayola sandwich tupperware because Eda told me the first half was enough. She “forced” me to forget my lunch in my locker during my high school lunch period, sometimes making me sit in the art classrooms to avoid food altogether. She used to link arms with me at recess and run next to me on the treadmill. Now, she picks out every outfit I wear and tells me when I can stop cycling every morning.

Eda is my eating disorder, my body dysmorphia, my self-loathing tendencies. She’s my obsession with the number on the scale, my BMI and how many calories I eat every day. She’s what forces me to compare my body to others, to measure my serving sizes and make sure I am eating less than everyone around me. She’s toxic, but she won’t leave, and sometimes I don’t want her to go.

It’s hard letting go of someone who has been a part of your life since you started learning how to add and subtract and the order of the colors in the rainbow. I still believe that Eda is the only one who tells me the truth sometimes, the only one who will keep me from getting any bigger than I already am, and if I let her go, who will hold me accountable for how much I eat and exercise? Who will help me find perfection?

There have been times where Eda left for a little while, didn’t visit to remind me to do pilates or come around when I decided to order cheese ravioli instead of a side salad. She was silent, and I didn’t miss her, but she always comes back, and she gets louder every time and reminds me why I “need” her, and, no matter how badly I don’t want to, I let her back in.

There have also been times where Eda has won the fight and caused me to lose weight rapidly, to shrink myself down to nothing but skin and bones and drop four dress sizes. Eda pulled me out of school and had me admitted to the hospital for three months, where she continued to tell me an apple had too much sugar and eating more than three peanuts would make my thighs grow three sizes overnight, where she made me hide Oreos from the nurses by pulling the cookies apart and sticking them to the bottom of the tables.

I silenced Eda that time. After being discharged, I made my way back up to a healthy weight and learned to stop labeling foods as “good” or “bad.” I let myself snack on Cheez-Its and go on ice cream runs with my family at 9 p.m. in the summer. I wore a bikini to the beach and didn’t feel bad about going back for seconds when Mimi made gravy for dinner.

But Eda’s back again now, and I’m ashamed to admit that I don’t think she will be leaving anytime soon. She’s persuasive, and she has my doctor and my therapist on her side this time. Before the start of the spring semester, my doctor told me my BMI showed I was overweight, that I could afford to lose 6 to 8 pounds. My therapist told me I shouldn’t be eating McDonald’s more than once a month if I didn’t want to die of heart disease. Eda agrees with both of them, and she’s convinced me that I do, too.

There exist dozens of positive voices in my life that tell me otherwise. My mom tells me I’m perfect, that my curves remind me of her when she was my age and that I should embrace my womanly figure. My dad tells me boys probably find me too beautiful and are intimidated to approach me. My friends tell me they would do anything to have a body like mine, that I have the end result people show their plastic surgeons and pay money to look like. I am constantly reassured of the fact that I am beautiful, but Eda takes these compliments in her boney hands and tears them to shreds.

Since Eda and I have moved back to campus for the spring semester, she has been the friend I’ve spent the most time with. In three weeks, Eda has helped me lose 19 pounds. She has restricted my calorie intake to less than 1000 calories a day, less than 500 if I’m not feeling lightheaded. She doesn’t let me leave my room without my Fitbit on my wrist, counting every calorie I burn and tracking every calorie I eat. She tells me I can’t eat anything but raw fruits and vegetables, and only if I am feeling too weak to make it to the end of the day. She’s controlling my every move, and I’m letting her.

It’s not that I want to. It’s not that I don’t want to listen to my best friend telling me I am going to end up in the hospital again if I keep following the path I am going down right now, or to ignore my family members constant texts and pleas telling me to “just eat” or they will pull me out of school again. I am not choosing not to listen, Eda is just louder, and she’s even meaner when I ignore her demands.

Eda’s strong, and Eda’s confident. Eda promises me that she will help me get to the point where I’m not the big friend anymore, the one who’s always hungry, the one who can clear her plate faster than anyone else and eat the most compared to everyone at the table, and I am willing to do whatever it takes to not be that friend anymore.

When my friends ask me to take a lunch break with them, Eda tells me I have too much work to do to get up and go. She knows staying busy keeps me away from food, and she knows food will make us spiral. When my friends ask me to go to our favorite restaurant, it’s easier for me to pack up half of my meal before eating than it would be for me to deal with Eda telling me to shove two fingers down my throat until my chips and salsa come back up.

I’m not ignoring the help my friends are trying to offer, I am protecting myself from what Eda will make me do if I do listen — sit in front of my mirror and pick and pull at my body for an hour before bed, cry on the bathroom floor in front of the toilet and tell myself that I need to keep my food down, call my mom for reassurance that it’s okay if I ate a normal amount today, that it’s impossible for me to have gained three pounds overnight.

Eda sets goals for me, and if I don’t reach them, the goals only get harder to achieve, and I only become more determined to satisfy her.

The number on the scale has plateaued, and Eda is mad. She wants me to lose at least 15 more pounds, but my weight hasn’t changed in more than a week despite the lack of food I am eating and the exercising I am doing, and because of the time I spent in the hospital, I know this means my body has entered fight or flight mode. My muscles are deteriorating, my body is holding onto fat to maintain homeostasis and keep me from collapsing at any given moment, and I can barely workout for long enough periods of time to see a difference in my body composition.

Yet, I still can’t get myself to eat a single meal.

I still can’t stop comparing myself to my best friend, who’s half my size and eats less than my 10-year-old sister. Or my other best friend, who skips lunch every day and thinks it’s okay because she’s been doing it since high school. I can’t stop the competition that my brain starts every morning, taking count of the calories each of my friends are consuming, how many times they’ve eaten, how long they’ve waited between meals, how many times they say something about what they’ve eaten, how many times others have said something about their eating. My numbers need to be the best in every competition category, otherwise I’ve failed again, and Eda helps me keep a tally.

Eda and I hyperfocus on the little things, the things nobody else would consider thinking about. They take up my entire head, no matter where I’m at or what I’m doing, the little things are on my mind. She skipped dinner and hasn’t eaten since 8 a.m. She only ate two of her French fries and didn’t finish her chicken nuggets. She counted a small coffee as a meal and only had two sips.

Everything I notice becomes another part of the game Eda plays with me. “Yeah, she may have only eaten two French fries,” Eda says, “but you’ve had none.”

Eda tells me these things are important and that they are the standards I must reach. If she only had coffee for breakfast, you’ll have nothing. If she only ate two tacos for dinner, you’ll have some applesauce, if you’re really that hungry.

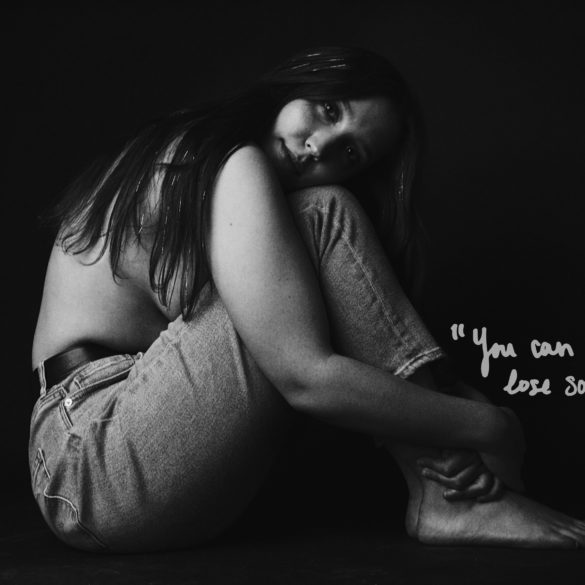

“You can’t start eating more until your friends do,” Eda says, “otherwise, you’ll always be the big one.”

There’s a routine Eda and I follow every morning after my alarm goes off. Stretch, get up, go to the bathroom, wash hands, brush teeth, brush hair, take off every article of clothing and weigh myself five times — maybe the more we do it, the lower the number will become. We follow the same routine again before bed.

It’s Eda’s favorite before-bed activity to check the scale and convince me that I have gained 2 pounds in 10 hours, to force me to strip down to my bra and underwear and sit in front of the mirror on my wall for another half an hour staring at the rolls on my stomach and the stretch marks on my side, flipping through old photos of myself and comparing every inch of me then to every inch of me now.

Eda sets rules for me every day to follow:

Don’t eat after 6 p.m. (or at all).

Cycle for at least 30 minutes a day. If you don’t, you’ll gain weight.

Eat less than your friends do. Way less.

Watch everything you eat, but watch what your friends eat closer.

I didn’t think Eda would still be my friend in college. I thought that after my hospitalization my junior year of high school I had lost Eda for good. Now, as a 21-year-old college student, I sit on my best friend’s floor and cry to her every night about how badly I wish I looked like her, I ignore the hunger pains in my stomach until I’m used to them and don’t feel them anymore, I smell food and tell myself that’s satisfying enough, and I fall asleep every night hoping Eda will give me the strength to get through another day without eating.

Eda makes me procrastinate on the things that matter most to me and instead spend my time scrolling through Instagram, comparing my body to photos of models and influencers with comments on their posts telling them they have no flaws. We watch videos of how to pose our body properly to give the illusion of a thigh gap in photos, or save Pinterest posts to boards dedicated to healthy recipes and workout circuits.

Eda ruins friendships by making it impossible for me to tell my best friends that the way they eat makes me feel like the biggest, most disgusting and unladylike woman on the planet, that their small meals make me despise myself and how big my appetite could be.

Eda makes me compare myself to every girl that walks past me on campus and analyze my appearance compared to theirs, to stalk my new roommates’s Instagram profiles just to tell me that they are skinnier and prettier than I am and that I’ll be the fat roommate again next year.

Eda makes my family worry and puts my parents in pain because they know their daughter is hurting and they don’t understand why.

Eda’s voice enters my head every night to try to convince me that I miss being small enough to be hospitalized. She whispers in my ear that my friends only keep me around because I am fatter than they are and it makes them feel good to not be the big friend in the group.

She doesn’t make life easier. She makes every day a war with my reflection.

I have people that help me fight Eda, people who question Eda’s intentions and try to talk me into fighting her off. But they give up on me quickly after trying to help because they don’t understand and it bothers them that I’m “not listening.”

I wish they understood that I’m not choosing not to do what they tell me. I’m not choosing to dissociate in the dining halls because there are people eating food all around me and I am starving but Eda won’t let me get food for myself. I don’t choose to have Eda speak for me and tell my friends that I’m not hungry when the almonds sitting on my desk are making my mouth water.

Eda paralyzes me. She blocks me from being able to enter the logical side of my brain and takes complete and total control over my body and mind, and there’s nothing I can do to get myself back. Tay’s not here anymore in those moments, and my friends and family don’t understand — but Eda does.

Eda remembers ballet class and the Bearcat Den. Eda remembers the chicken-scratched notes she pulled out of my desk every day and comments our classmates made about my body and athleticism. She remembers comments from her family telling her to eat slower, to work on portion control and lower her appetite. Eda was there when I was getting compliments for losing so much weight so fast. She remembers how they made me feel, and she’s addicted to helping me feel that way again.

Eda is here to stay. She will always be a part of who I am, and while she may disappear at times, her voice is always in my head, her thoughts are always trying to take control, and sometimes she’s strong enough to crawl her way back into my brain and convince me that I need her again.

Recovering from Eda is a constant process. There is no end, no finish line, no final level to clear Eda and kill the villain. She will be with me forever, and while it may not make complete sense why I can’t let Eda go, I hope that introducing you to her will at least help to remind you that sometimes Tay will bring a plus one to dinner.

So, make room, pull up an extra chair and welcome them both to the table. They’re trying their best.