Like half of all Americans, WaTasha Barnes Griffin survived an abusive relationship. Now, she uses that experience to help others escape crisis.

* Editor’s note: At the request of WaTasha Barnes Griffin, Ball Bearings agreed to change the name of her previous boyfriend for this story. Separately, the reporting for this piece was completed before WaTasha announced her candidacy for Muncie City Council.

The woman waited. With a duffel bag to her side and a rainbow-colored pillow in her lap, she waited in a lounge of the shelter she’d stayed at the night before. She was waiting to meet with someone from the other shelter, the one across the street, the one they told her was best for helping people who faced domestic abuse—people like her. She waited there because she was tired of waiting for things to change, for the chance to feel safe in her home, for it to be the last time he did it.

She was afraid he would find her, but she had waited long enough.

After leaving her partner the night before, she had gone to the police, who took her to YWCA Central Indiana. The Muncie-based shelter provides safe housing for women and children, including many who are fleeing domestic violence. But because the neighboring nonprofit, A Better Way, focuses on helping abuse survivors, the woman chose to seek long-term housing there.

Walking out of her office, WaTasha Barnes Griffin noticed the waiting woman.

Hi, I’m WaTasha, she said, walking up to her. I’m the CEO here at the YWCA. How are you doing?

Hi, I’m WaTasha, she said, walking up to her. I’m the CEO here at the YWCA. How are you doing?

I’m waiting to meet with someone from A Better Way, the woman replied.

Oh, I actually used to work there, WaTasha said. She told her more about the organization and its services, that it was a great place with great people. But she could see it wasn’t enough to calm the woman’s fear.

You know, WaTasha said, taking another route, I am a survivor of domestic violence, too.

The woman’s eyes widened. Really?

Yeah, WaTasha answered. That’s how I know it will get better.

More than a third of women and a quarter of men in the United States have been raped, physically abused, or stalked by intimate partners at some point in their lives, according to the National Domestic Violence Hotline. Even more Americans—nearly half—have experienced psychological aggression. On average, survivors try to leave these relationships seven times before staying away for good.

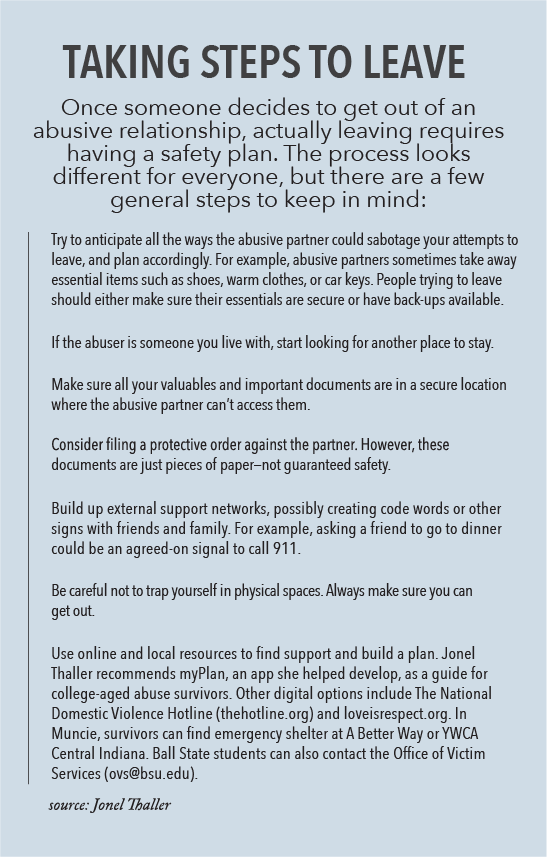

Jonel Thaller, an assistant professor of social work at Ball State University, says leaving an abusive partner can be confusing and time-consuming. Having a desire to leave doesn’t make it easy, and even coming to that decision can be a complicated process. According to The Hotline, some survivors who never learned what a healthy relationship should look like might believe abuse is normal. They might start blaming themselves or feel too ashamed to seek help. Others just feel too dependent on their relationships, mentally or financially, to consider walking away.

Plus, even while enduring abuse, a lot of survivors still care deeply about their partners. They love them. And when you love, you forgive, you hope, and you wait.

WaTasha first fell for Brandon* when she was a sophomore and he was a junior at Muncie Central High School. He had that magnetic sort of charm: a charismatic football player in Timberland boots and Drakkar cologne.

He made WaTasha laugh. They both liked Aerosmith and LL Cool J. They bonded over root beer floats and the autobiography of Malcolm X. But it was his brown eyes that really got her: She thought they were beautiful.

“Things were great,” she says. “And then little by little, things started to change.”[epq-quote align=”align-right”]“Things were great. And then little by little, things started to change.”

-WaTasha Barnes Griffin[/epq-quote]

About a month into their relationship, Brandon brought up WaTasha’s friend Travis, asking why she had been talking to him after school one day.

Travis? she said. We grew up together. He’s my best friend.

Why do you have a guy as your best friend? Brandon asked.

I don’t know, WaTasha said, surprised at the question. He just is mine.

For months, those concerns about Travis kept coming, dominating their conversations. Brandon always wanted to know where WaTasha was. If he called and she didn’t answer, he’d ask about it later. He always wanted to be with her, and she started to feel like she couldn’t spend time with anyone else.

Abuse is about control, Thaller says, which can stem from a fear of abandonment.

“They are looking for their partner to fill their every need,” she explained, “and they’ve gotten to a point where they’re demanding it.”

If a relationship limits a person’s power or freedom in any way, that should be a red flag. While Thaller says jealousy is normal, when one partner tries to restrict the other’s choices and who they spend time with, that’s probably abuse.

WaTasha saw the red flags, she says, but she ignored them.

One afternoon, Brandon was parked in his white Nissan, waiting to take WaTasha home from school. She doesn’t remember what took her so long to gather her things—she was probably talking with friends, she says—but when she came outside, Brandon was convinced she had been making plans with Travis.

As they drove away, Brandon didn’t let it go.

Why do you hang out with him? he asked, his voice growing strained. Do you not want to be with me anymore?

WaTasha pleaded with Brandon. She needed him to understand that Travis was just a friend. He shouted back, not accepting the answer.

Then, he slapped her in the face.

Don’t you yell at me! he screamed. Sitting stiff in the passenger seat, WaTasha didn’t know what to think. But she was scared, and she needed to get out. They were only a few blocks from her house, so she demanded he take her home. Brandon immediately apologized, saying he was sorry, that he loved her and just wanted to be with her. She stared out the window.

When she got out at the curb by her house, Brandon said he would call her later.

Don’t, WaTasha said. I’m done. She turned and walked inside.

After putting away her bags, she came out and looked at her mom. She didn’t cry—she just told her.

Brandon hit me.

What?

He hit me. She explained what happened.

WaTasha, that’s…abuse, her mom said.

WaTasha’s parents called Brandon’s, and both families agreed the relationship would be over. For a few days, it was. But Brandon never stopped trying to talk with WaTasha, and one day during lunch, she gave in.

Brandon apologized again, saying he had been having a bad day. He blamed the stress of sports and grades, said he loved her, and asked her to come back.

Okay, she said. Just promise me you won’t do it again.

WaTasha doesn’t remember exactly when the next hit happened, but it wasn’t a slap. Sometimes he would shove her. Other times he’d grab her arm, or clench her face in his hand. Every time, she would find a way to justify it.

WaTasha doesn’t remember exactly when the next hit happened, but it wasn’t a slap. Sometimes he would shove her. Other times he’d grab her arm, or clench her face in his hand. Every time, she would find a way to justify it.

Brandon was always there. And if he wasn’t, he would call her. If she didn’t answer, he’d confront her about it later. Even when things were good, WaTasha always wondered when the next argument would happen.

Thaller says people might only think of abuse in terms of physical violence, but the verbal and emotional attacks can be even more damaging. When someone you love controls your actions and belittles your choices, it can make you feel helpless.

Every time Brandon abused WaTasha, she decided she was done. But every time, he would come to her, crying, asking her to just listen. He’d say he was sorry, blame it on the stress, buy her cards, write her letters, or ask her to the movies. He once even apologized to her parents, who had filed police reports and protective orders against him. And every time, WaTasha listened. She would remember how funny he was, and how much she loved telling him about the last book she read. She’d look into those brown eyes and fall in love again.

“I would just go back to the beginning,” she says.

According to a Counseling Resource article by psychologist Joseph M. Carver, when a person grows used to being abused, even small acts of apparent kindness can create positive feelings that strengthen the bond. Survivors might start seeing things through the abuser’s perspective, predicting how their partner could respond in certain situations and making choices accordingly. But they can’t predict everything.

During one of the times WaTasha and Brandon were broken up, she was coming home late and parked across the street from her house. It was dark, so she didn’t see Brandon at first. But walking up the driveway, she stopped short: He was there, sitting alone on the bottom porch step. Three more steps separated him and her front door.

Where you been, Wo? That’s what he called her.

What the hell are you doing here? she asked, terrified.

I just want to talk to you!

You have got to go, she said.

Brandon stood and grabbed her shoulders hard, shaking her. Just listen to me! he pleaded. Why are you acting like I’m going to hurt you?

WaTasha tried to get past him, to get to those three steps. She threatened to scream but never did. Eventually, he just let go and left, down the drive and around the corner.

Heart racing, WaTasha climbed the steps and went inside. This time, she didn’t tell her parents—she just went straight to her first-floor bedroom and locked all the windows, hands shaking on the latches.

WaTasha knew the relationship wasn’t healthy. She’d been raised to know that, taught to stand up for herself, told to be strong. But sometimes, it just felt easier to go back. If she was with him, she didn’t have to deal with his questions or worry that he’d find her. It was when she left that she had to watch her back.

An end to the relationship doesn’t mean an end to the danger, Thaller says. Abusive partners might continue to stalk or harass the person for a long, long time. Sometimes, the abuse could even get worse. Survivors have seen what their abusers are capable of, so when they’re scared of what could happen if they leave, many will find it easier to focus on the good times and believe things will get better on their own.

Thaller says it’s important to trust a survivor’s judgement of when it’s not safe to leave. Even if the person hasn’t taken clear actions to end the relationship, that doesn’t mean they aren’t preparing. For example, they might be working to imagine life without their partner, planning solutions to the obstacles they know might get in their way. They might be working beneath the surface to disconnect, to break that emotional bond.

WaTasha broke up with Brandon more than 10 times in their two-year relationship—more than 10 times that he’d follow her to the mall, show up at her house, or take the spark plugs out of her car while she was at work. They broke up so many times, WaTasha can’t remember why they’d split up the July before her senior year, while her parents were away, and she was home alone on a Friday afternoon.

Earlier that day, she’d warned her brother not to answer the phone or open the door.

Brandon is driving me nuts, she explained to him. You know how crazy he is. But her brother left to play basketball and didn’t lock the door behind him.

WaTasha was sitting in the living room when she heard the door open, and she thought her brother had come back. Instead, it was Brandon who walked around the corner.

WaTasha jumped. How the hell did you get in my house? she yelled.

Brandon chuckled. The door was open.

She yelled at him to get out, threatening to call the police and running toward the phone. But Brandon blocked her, darting back to the kitchen and pulling the cord from the wall.

You are going to listen to me, he said, clutching the receiver in his hand, one way or the other.

WaTasha turned, going for the phone in the living room, but Brandon was too fast. Then he stood in the hallway, using his football build to block WaTasha from the last two phones.

They screamed at each other for nearly an hour. You are gonna be with me! Brandon yelled. Listen to me! You are always going to be with me. You’re mine.

WaTasha cried, telling him to leave her alone. And when she looked into his eyes—those brown, beautiful eyes—she saw something was different this time. She knew she had to get out.

“He didn’t push,” she says. “He didn’t shove. But he was saying all kinds of things, and I was scared.”

Eventually, Brandon needed to go to the bathroom, and he made WaTasha come with him so she wouldn’t run. But as soon as he unbuckled his jeans, she sprinted down the hall, out the front door, down those three steps, and to a video store across the street. She ran behind the counter.

Look, she told the workers, my ex-boyfriend is in my house, and he is acting crazy.

Before they could do anything, Brandon walked in.

Make him get out, she pleaded. Make him leave, or I’m gonna call the police.

Brandon tried to say WaTasha was lying, that he’d just come to her house to get his jacket. But when the workers told him to leave, he did.

The police came, made a report, and escorted WaTasha back to the house. After making sure Brandon wasn’t there, they promised to stay nearby while she waited for her aunt to pick her up. This time, all the doors were locked, but it didn’t take long for Brandon to come back and start knocking on the windows. WaTasha just ignored him and waited.

Her aunt came around 4:30 p.m., and they packed to leave. Brandon was still there, standing by the steps, and he followed the car to the bottom of the driveway.

That’s fine, you go with your aunt, he said, laughing. We’ll get back together.

No, we won’t, WaTasha said through the passenger window.

We will. We always do.

They drove away, and WaTasha said she was done with Brandon. You always say that, her aunt replied.

But this time, it was true. This time, she would prove them both wrong.

Brandon never stopped talking to WaTasha, but after that day, she stopped listening. She spent time with friends and stayed away from places he could find her. She started seeing another guy, for a while—it wasn’t serious, but it helped her move on. Now, for more than 25 years, Brandon has always been there—confronting her at the grocery store, contacting her on social media, calling to say he would come to the church and stop her wedding. (He didn’t, and she’s been married 17 years.)

Today, as WaTasha helps others find their way out of crisis, it’s as more than a service provider. She hears their stories and connects, survivor to survivor, with their trauma and their fear. She knows how subtle abuse can be. She knows how hard it is to leave.

For the woman who’d been waiting in the lounge, hearing WaTasha’s story wasn’t a quick fix for the fear. She was still scared of her abuser, still not sure she would be safe. But despite the weight of that fear, and of not knowing what would come next, WaTasha watched the woman leave with the strength of knowing she wasn’t alone.