Despite some individual efforts to protect the Earth, the politicization of environmental issues can slow down real progress.

It was the kind of perfect weather you had to be happy about. It was warm and breezy in San Francisco, and I stood on the Embarcadero waiting for the old streetcar to stop and pick me up. On a clear day like this, I could look past the cars on the street and the pier, all the way across the San Francisco Bay to Berkeley.

Interrupting the moment, I got a text that immediately sent me into a panic. My stepmother told me that a fire had started on a hill less than a mile from our house. The residents of the neighborhood nearby were ordered to evacuate.

Fires like this one are a somewhat normal occurrence in northern California. During the 10 weeks I spent there for an internship in the summer of 2018, the sun was often clouded by smoke, sometimes causing a cough or a full-blown cold. These neighborhood infernos can quickly grow from a Friday night inconvenience to a complete catastrophe.

I grew up in rural Illinois, the home of spring thunderstorms and tornadoes. The occasional rotating funnel clouds of debris didn’t bother me much, though. They’re fairly predictable for natural disasters and usually don’t do much damage.

My dad and stepmother moved to the California Bay Area in 2017. When I visited them over spring break, they briefed me on their earthquake emergency plan: Stop what you’re doing, and meet at home. I never got a fire emergency plan. Was I still supposed to go home?

Would there even be a home to go back to?

My parents, true Midwesterners deep down, didn’t have much experience with wildfires, either. My dad ran around the house grabbing loose cash. They didn’t have emergency bags prepared in case of an evacuation.

Pre-fire, my stepmother and I had planned to go shopping. She and my dad were flying to Illinois for the Fourth of July, and she needed to grab a few more things. At her request, I continued the afternoon as planned and took the train home. During the ride, I wondered if the other passengers knew we were heading toward a fire. I wondered if any of them were racing home to ashes. And if they did know, did they care? Was the news of a wildfire something you ignore until it’s a mile from your cul-de-sac?

Out the window, I could see a section of Mount Diablo painted red from flame retardant. A helicopter with a hose hanging out the side passed overhead. I discreetly snapped some pictures through the smoke-stained window, trying not to let on that this was my first California wildfire.

According to Cal Fire, wildfires have burned across more than 620,000 acres in California this year, compared to 311,000 acres during the same timespan last year.

“It is the changing climate that is leading to more severe and destructive fires,” said Scott McLean, deputy chief of Cal Fire, in a statement.

The Problem With Politics

In late 2015, leaders of more than 190 countries made their way to Paris for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Out of this meeting came the Paris Agreement, a document signed by 175 countries promising to lower greenhouse gas emissions and increase sustainability. This agreement, the first of its kind, bound countries to behaviors that would hopefully reverse the impacts of climate change. Or would it?

Former President Barack Obama officially adopted the agreement in September 2016 by signing an executive order. By doing this, he bypassed the Senate approval needed for treaty signing. When President Donald Trump announced the United States would abandon the Paris Agreement in June 2018, experts debated whether or not we actually could “leave.” Since we didn’t join by traditional standards, we might not have ever technically been a part.

Regardless, many countries have been urging the U.S. to rejoin the pact. In September, representatives from 18 Pacific Island nations met, trying to convince the U.S. to return.

If the goal is to reduce worldwide greenhouse gas emissions, the U.S. would have to comply. The U.S. is the second-greatest emitter behind China, which released more than a quarter of all greenhouse gases in 2013.

Overwhelming scientific evidence points to the warming of the planet, but the politicization of the issue slows any action in the U.S. Jeffrey Dukes, director of the Purdue Climate Change Research Center (PCCRC), believes the political stigma now tied to climate change makes it harder to address.

“Climate change became political, making it difficult to have a rational conversation,” Dukes says. “It’s not a science problem. It’s not really an economic issue. It’s politics.”

Waste Not, Want Not

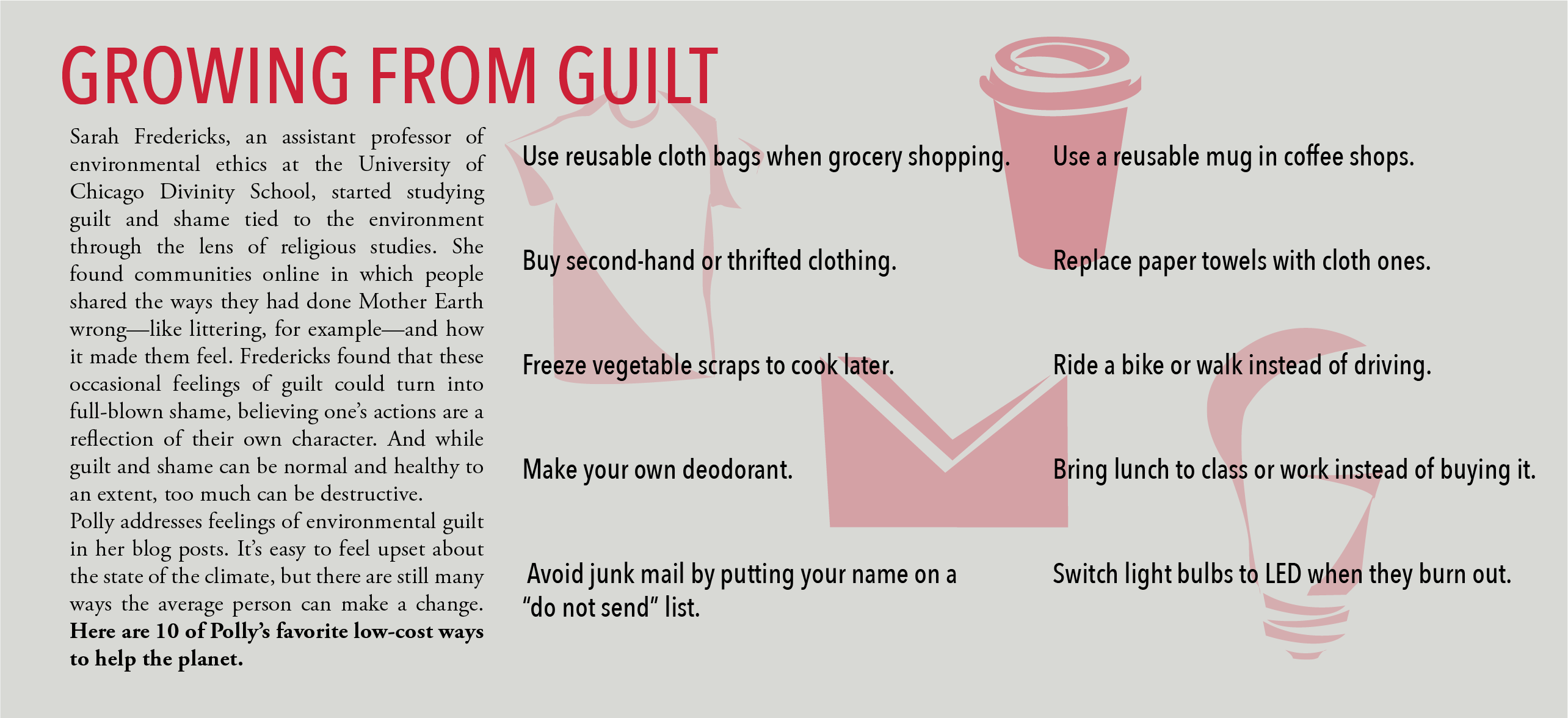

In 2015, Polly Barks decided to live waste-free. A blogger located in Indianapolis, she says there were lots of reasons she wanted to make a change—large amounts of littered trash and food deserts were big ones.

“Coming face-to-face with the trash build-up that happens in low-income communities made me realize trash didn’t ‘go away,’” Polly says. “It just goes away from us privileged enough to be able to avoid the problem.”

Polly’s decision to live zero waste, though very personal, had a positive impact on the environment. By cutting out the use of plastics, Polly would reduce the number of microplastics in the Indianapolis area soil and water. By replacing disposable day-to-day items, such as straws or utensils, she would decrease the chance of that waste ending up somewhere harmful. And these changes weren’t just good for the environment—switching household or beauty products proved healthier for her, too.

In 2017, Polly started Green Indy, a blog for advice on living zero waste. While Polly’s tips are helpful to anyone hoping to make a change in any state, Polly does believe that living zero waste can be more difficult in Indiana than in other places.

“Indiana is not environmentally friendly at a governmental level,” Polly says, “so making big changes is really hard. Cultural and institutional apathy for environmental issues is hard to overcome.”

Still, Polly says individuals can work to reduce their own waste. Personal choices, such as reusing grocery bags or bringing a travel mug to coffee shops, can be made in any political climate.

Hitting Home

When people think of climate change, they think of polar bears. Melting glaciers. Rising sea levels. Melissa Widhalm, the operations manager of the PCCRC, wants people to think of things they love from where they live. The Indy 500. The Indiana State Fair. Softball in the summer. These are the things climate change would affect in Indiana.

It’s difficult to picture what climate change would do in the Midwest—or, more realistically, what it has already done. Researchers at the PCCRC found that Indiana has already experienced warming. In addition, the growing season has lengthened and precipitation has increased, primarily from heavier downpours.

While these changes don’t seem as dramatic or theatrical as wildfires or disappearing ice caps, they’re still detrimental to people, agriculture, and ecosystems in the state.

Take the Cisco fish, for example. This coldwater species used to live in 50 lakes in Indiana, but now can only be found in about five. A slight rise in temperature was enough to reduce the population size. Rising water temperatures and an increase in algal growth will most likely kill off all the Cisco in the state, Dukes says.

This heat won’t stop at destroying native species. Experts at PCCRC anticipate new mosquitoes and ticks will move further north, likely carrying diseases. This public health issue could be a reality with only a one or two degree increase in temperature.

If you ask Dukes or Widhalm, or just about any other scientist studying the effects of climate change, this is a situation that requires action now. In October, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) released a report that the world will rise in temperature by 1.5 degrees Celsius (or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) between 2030 and 2052. This seemingly small change will cause more intense storms, decrease our wheat and corn crop yield, and raise sea levels by 40 centimeters by the end of the century. Fixing this problem would require widespread changes in institutions, governments, and economies all over the world.

Experts agree that these big-picture changes need to be made to truly slow or stop climate change. Investing in clean energy and restructuring corporations for sustainability are some of the goals. But first, people need to have conversations about these changes.

“This makes me feel awful. This is scary,” Widhalm says about PCCRC’s climate findings. “Hope gets lost. But these are solvable problems.”

And in the meantime? “Use your voice. Vote. It might not make you feel good, like turning off that light,” Widhalm says. “Always remind yourself that it can be solved. Everyone wants to do the right thing—it just needs to be discussed.”

A correction was made to the online story. In print, the story reads that 1.5 degrees Celsius is 34.7 degrees Fahrenheit. The story has been corrected to read 1.5 degrees Celsius (or 2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).