Hurricane Maria caused $102 billion in damages. Today, the island nation is still recovering and navigating its new normal.

First, there was Irma.

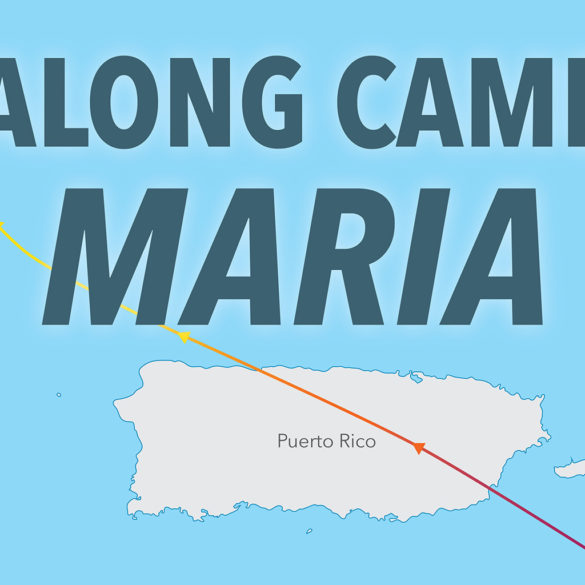

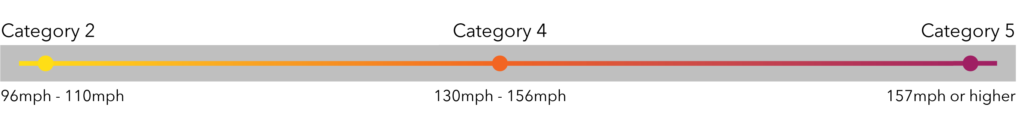

Hurricane Irma was a Category 5 major hurricane that swept through the Atlantic region on Sept. 6, 2017. According to the National Hurricane Center, it claimed 129 lives and triggered 25 tornados, mainly in Florida.

For the most part, Puerto Rico was largely unaffected by Irma. Islander Peggy Sachs Feliciano had her power and water service knocked out for two days, and she experienced heavy rain. But it wasn’t anything she hadn’t seen before at her home in Lares, a small municipality located on the upper northwest side of Puerto Rico.

Then, there was Maria.

Hurricane Maria made landfall in Puerto Rico on Sept. 20, 2017, exactly two weeks after Irma invaded Florida and the Atlantic region.

In the days leading up to the storm, Peggy scoured the news for the latest reports about the then-Category 5 hurricane.

Some weather reporters said the hurricane would pass to the north and completely miss Puerto Rico. But Ada Monzón, a meteorologist from San Juan who specializes in hurricanes, said Maria was going to hit hard, and residents should prepare in any way they could: board up their houses, stock their pantries, and dig out their Red Cross radios.

When it came, this hurricane was different. Maria’s winds howled louder than anything Peggy had heard before. She says it was like the sound of an airplane engine about to take off when you’re sitting close to the wings.

Maria came down with all her fury, Peggy says.

There was more rain than she could process. The moisture seeped through her roof and ruined two bedrooms in her three-story house. The island received more than 20 inches of rain in five days, according to AccuWeather.

Maria took more than just the island’s electricity and residents’ sense of security. According to an estimate by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Maria cost Puerto Rico and the United States Virgin Islands $90 billion in damage, following Katrina and Harvey as the third-costliest hurricane in the United States. George Washington University determined that the storm and its aftermath killed almost 3,000 people.

Maria Makes Landfall

Peggy and her family didn’t prepare much for Maria, since they’d already prepared their home for Irma a mere two weeks prior.

To hurricane-proof her house, Peggy used plywood and planks of zinc to cover her windows and doors. She moved her car to a friend’s garage, where it wouldn’t be susceptible to wind or water damages. To finish off her preparation, she tied her roof down with cables and filled empty containers with water. This way, she’d have a way to wash, clean, and flush her toilet.

Peggy was used to hurricanes. Since moving from New Jersey to Puerto Rico 30 years ago, she’s experienced five major hurricanes and countless tropical storms first-hand. She thought she knew what to expect from Maria.

But when it made landfall at 6:15 a.m. on Sept. 20, 2017, it was one of the longest days of Peggy’s life. She and her family took shelter in their home office for more than 24 hours. By 8 p.m. that evening, she was desperate for it all to end.

Shut up, Maria! We can’t take it anymore! she would yell, all while cleaning up storm water that had made its way into her home.

The hurricane’s 155 mph winds were the worst part of the whole storm, at least to Peggy. At one point during Maria, she looked through the window to see something flying off the house.

Oh look, she said. There goes our roof.

At the end of the day, they laid down to sleep with soaked clothes and sore ears. Her son tried to block out the sound of Maria’s howling winds by covering his head with a pillow. Her daughter did the same with a blanket.

None of them slept that night.

A Different World

When Peggy first stepped outside after Maria had settled down, what she saw looked like a different world.

Trees and power lines wove together. Debris blanketed yards and streets. Fallen trees and thick shrubbery covered the ground, giving the Puerto Rican land a jungle-like feel. Maria’s rain left Peggy’s backyard looking more like a wetland than a homestead.

She felt alone.

Peggy tried to get a signal with her Red Cross radio, but she couldn’t pick up anything. It felt like the whole island was silent.

At first, Peggy thought her area was the only one without power. She’d lived through plenty of storms, so she’d expected the power to go out. But after talking with others in her community, she realized the lights were out in all of Puerto Rico.

Exactly one day after Maria made landfall, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reported having 3,500 staff members on the grounds of Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands to help with relief efforts. The following day, that number grew to 7,000.

By Sept. 23, 2017, a U.S. navy ship was headed to the two islands, carrying over one million meals and one million liters of water. FEMA’s federal reports also show 180 Red Cross volunteers and staff members being in the Caribbean at the same time delivering aid.

Six days after Maria made landfall, FEMA says it had 32 commodity distribution points between Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.

But according to Peggy, “San Juan got all the help.” She didn’t see any relief efforts in her community until nearly a month after the storm. She says it was the citizens who cleared the streets, and the same citizens who gave neighbors water and food.

“It was us taking care of each other,” Peggy says, “because the government was nowhere.”

Eventually, relief did come to Lares. But it wasn’t what residents expected. Peggy says each resident received a box of supplies, labeled as containing 10 entrees, 10 fruits, 10 waters, and 10 flatware.

But when Peggy opened her box, she only found Snickers, Butterfingers, chips, Poptarts, and pretzels.

This is not food, she thought. This is junk.

By December, three months after Maria, Peggy was still without electricity, internet, and a refrigerator. She refers to these months as The Walking Dead, based on the TV series by the same title. She even began a mini “blog” on Facebook to document the gloomy and confusing months that followed Maria.

To feel more normal, Peggy and her family would visit places that had their power restored. There, they felt included, like they were part of society. But once home, Peggy felt forgotten.

“We were abandoned over here,” Peggy says. “We felt isolated.”

On Jan. 1, 2018, Peggy’s home was the last in her neighborhood to have power restored.

More Storms, More Money

More than a year since Maria, Peggy’s room still isn’t repaired. She can’t afford to fix the damages right now.

According to the NOAA, the U.S. spent $306 billion on natural disaster damages in 2017. Prior to that, 2005 was the record holder, totaling $215 billion. It was the same year Hurricane Katrina tore through the Gulf Coast.

The rise in disaster-related expenses is partially due to an increase in people living in locations that are most susceptible to natural disasters, such as the coastal cities where Hurricane Katrina hit. According to Jill Coleman, a geography professor at Ball State University, many coastal homes don’t have the safest structures. When natural disasters arise, it doesn’t take much for those houses to be swept away by wind or water.

Another reason the U.S. is spending so much is because there are more natural disasters being recorded.

According to EM-DAT, an emergency events database that contains worldwide data on the occurrence and impact of natural disasters, the number of natural disasters has nearly tripled globally since 1978. Much of this increase is from climate-related events, which include hurricanes, droughts, flash floods, cyclones, and severe storms.

Puerto Rico Today

Today, Peggy’s home is infested with black mold caused by flooding. A blue tarp covers her roof. Driving through her neighborhood, she sees a lot of roofs draped in tarps.

Looking across the street, she sees electrical wires still lining the ground, their poles leaning. She’s scared those poles are going to fall on a car.

There are still piles of debris and places where people are dumping broken stoves, refrigerators, and mattresses.

And when the electricity goes out, as it often does these days, people panic.

Peggy is still open to humor, though.

Prior to Maria, she bought a pack of toilet paper and put it in her pantry, assuming it would stay dry. Despite that specific preparation measure, the hurricane’s water found its way in and dampened all her toilet paper.

Some things you just have to laugh at.