Ball State has lived 100 years. Here’s how they did it.

When Valerie Birk strolled down Ball State University’s McKinley Avenue as an undergraduate student in the 1980s, the main road seemed empty. The present-day Ball Communication Building was nothing more than an open field. Shafer Tower, the 150-foot, freestanding bell tower and unofficial campus landmark, wouldn’t be dedicated for nearly 20 more years.

“Walking by there was like walking by wasteland,” says Valerie.

Valerie has now served as an apparel design professor at her alma mater for 26 years. Since graduating, she has seen seven university presidents sworn into office and six resident halls built. She watched Ball State transform from a campus known for its teachers college into a university renowned for its telecommunications and business programs. As a student, she stood in line for seven hours some semesters to register for classes, while her students today can enroll online in a matter of minutes.

Over the course of her time at Ball State, Valerie has seen the university change with the evolving world around it. She’s seen the university sustain itself and make it to its centennial celebration—100 years of operating as an academic institution in the Muncie community.

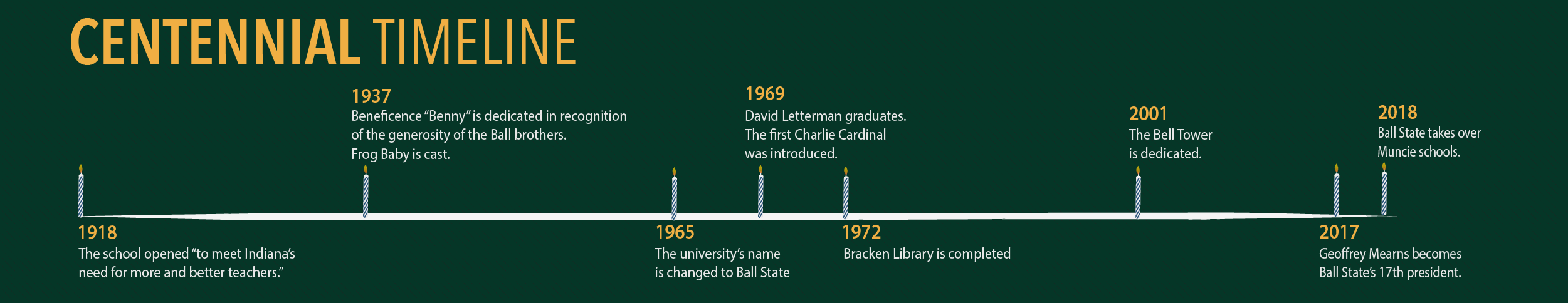

Universities don’t achieve longevity overnight. Ball State didn’t even achieve it on its first try. According to the Ball State history page, four private colleges opened and closed on the property between 1899 and 1917 until Ball State was founded in 1918. To make it to the 100 year mark, the university had to conform to students’ ever-changing needs, transform its curriculum, and ensure enrollment rates stayed steady.

Jay Halfond, a professor at Boston University, says successful universities “attract enough students to pay the bills.” The more students a college enrolls, the higher it ranks, and the more funding it receives. But competition among other universities to become more sophisticated in student recruitment and online distance learning can make attracting those students more challenging, says Halfond.

As more students migrate toward online and distance learning alternatives, universities have to adapt to maintain enrollment. According to a survey by Babson Survey Research Group, 30 percent of higher education students took at least one distance education course in 2016. Since last year alone, there has been a 5.6 percent increase in the number of students enrolled in distance education courses. This increase is attributed to the convenience, accessibility, and lower costs that online courses offer students who might not be able to attend otherwise. For universities, it means steady enrollment rates and satisfied, paying students.

According to the Ball State Fact Book, the university has increased its number of undergraduate students pursuing online degree programs by 62 percent since 2013. Nonetheless, Ball State has had no issue keeping up with its on-campus enrollment. Since 2015, the university has been steadily increasing its number of in-person undergraduate attendees every year.

In addition to becoming more accessible through alternative modes of education, universities must adapt to changing social and economic climates. Ball State did just that in the 1970s when Indiana experienced a teacher surplus.

According to the Ball State history page, the university opened in 1918 “to meet Indiana’s needs for more and better teachers.” For a long time, it was the degree that the university was most known for. When the teacher surplus hit Indiana, Ball State chose to improve another one of its programs.

E. Bruce Geelhoed, a history professor at Ball State, says the university took this opportunity to strengthen the business college. In doing so, the university steadied enrollment rates and added diversity to Ball State’s curriculum.

The university was interested in the business department because of its better job prospects. He explains that in the 1970s, Ball State introduced its entrepreneurship program, which became an added strength to the Miller College of Business.

Jayson Jarrett, an academic advisor for Ball State’s Miller College of Business, says this was possible because the college expanded its most popular major, business administration. The college also added concentrations, such as finance, insurance, and business management, which better prepares students for specialized fields. The college eventually became certified by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. According to the Miller College of Business, less than 5 percent of the world’s business schools have earned this accreditation.

Soon, the university will once again shift its academic focus, this time to science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) majors.

In an effort to expand its STEM programs and provide educational opportunities to students in this field, Ball State was awarded an $87.5 billion grant from the state of Indiana to build a new 175,000-square-foot STEM and health professionals facility. In an article released by the Board of Trustees in late 2016, it says it’s the college’s hope to attract more STEM students and produce graduates that represent the future of health care, “resulting in a more unified, less fragmented system—and better patient care.”

But a university getting to its centennial takes more than construction projects and program additions. It takes leaders, such as past Ball State President, Jo Ann Gora.

Gora is credited by two university professionals as getting Ball State to its centennial. Valerie and Jarrett both believe that Gora made one of the biggest impacts on the school to date when she served as university president from 2004 to 2014. Valerie remembers Gora as being “really thoughtful in her vision for Ball State’s future.”

Jarrett describes how Gora spent a lot of her time lobbying for money in the university’s budget. He explains that at most public universities, the president addresses legislators at some point about issues pertaining to their campuses, such as funding. Gora spent more than $520 million in updating the looks of Ball State’s campus.

Money is often a deciding factor for if a university can make it to its centennial. After all, not all universities make it that long.

According to Halfond, universities are forced to shut down when they are unable to pay their operating expenses with their net tuition income. In other words, when universities can no longer pay their bills. Halfond says some schools are “discounting” tuition or cutting academic departments to stay running, but that typically doesn’t make a difference.

For example, Saint Joseph’s College, one of the oldest universities in Indiana, was forced to close in May 2017 due to debt. The college was established in 1889.

“Once a school starts a downward spiral, it’s hard to reverse,” Halfond says.

Valerie has been fortunate enough to have never witnessed a “downward spiral” at Ball State. Although the university’s initial founding was rocky and unsuccessful on multiple accounts, it has turned into one of the largest universities in Indiana over the course of 100 years.

Ball State has changed a lot since Valerie was a student in the 1980s. But one thing that hasn’t changed for her is the number of smiling faces she sees around campus.