With the rising threat of mass shootings, schools consider how to best plan for emergency situations.

Heather Kasselman has two sons who attend elementary school and daycare in Noblesville, Indiana. On May 25, 2018, she and her father-in-law were driving south toward Indianapolis for Indy 500 festivities when they suddenly saw police cars speeding north toward Noblesville.

Normally, she wouldn’t have thought anything of it. But in this instance, she was overcome with dread. A call from her son’s school quickly confirmed her suspicions: There was a potential gunman in the area.

Hopelessness flooded Heather. It would do little good to drive to the school, and all she had were news updates and messages from her son’s first-grade teacher. She says the details of that day are all a blur, but she will never forget that feeling of desperation.

Although this threat left Heather’s sons unharmed, on that Friday morning, a 13-year-old student had brought a gun to Noblesville West Middle School. He shot and injured his fellow student, Ella Whistler, and teacher, Jason Seaman, who then wrestled the student to the ground.

The Noblesville attack marked the 23rd school shooting in 2018 in which someone was injured or killed. As these types of incidents receive more attention, school faculties are forced to take new precautions to prepare for shooters and other potential threats.

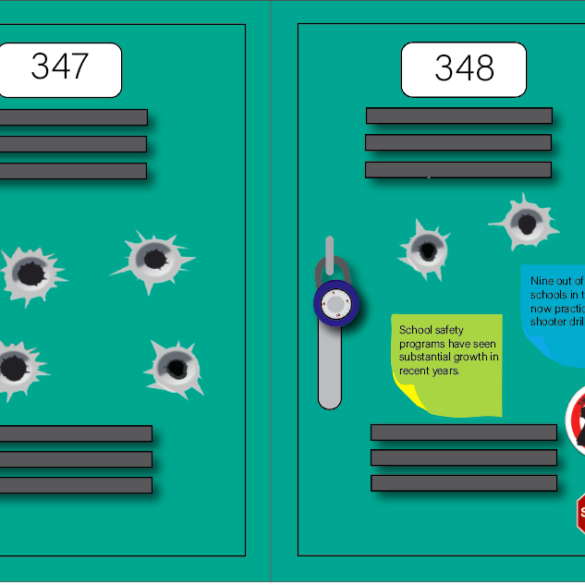

According to the National Center on Educational Statistics (NCES), nine out of 10 schools in the U.S. now practice school shooter drills. Different schools, though, create different preparedness plans. Some tell students to hide in the dark and stay quiet, while others are taking steps toward more hands-on strategies.

School safety programs have seen substantial growth in recent years; when the NCES began collecting data in 2003, 79 percent of schools had established procedures for the event of a shooting. By the 2015-2016 school year, this number climbed to 92 percent.

Heather says the lockdown protocols at her sons’ schools are pretty standard and similar to what they were when she was a music teacher just two years ago—get to a safe place, turn off the lights, lock the doors, and wait for further instructions.

As a former educator, she says that, while teachers might act heroically in the throes of a tragedy, most are in no way trained to do so. During her seven years as a teacher, she received little to no training besides to turn off the lights and take cover until you hear the “all clear.” She feels this response is no longer enough.

Safety Divided

Like Heather, Amanda Klinger agrees such general approaches to school safety aren’t always sufficient. As director of operations at the Educator’s School Safety Network (ESSN), a national non-profit specializing in resources for violence prevention and crisis response, Klinger feels the current government actions being taken to address the issue might be the wrong direction altogether.

In July, Gov. Eric Holcomb released a school safety update for Indiana that announced a new program to offer free, handheld metal detectors to schools. On a national scale, the STOP School Violence Act passed the U.S. House of Representatives in March of 2018. This bill offers an annual state-based $50 million grant for implementing training programs for students, teachers, and law enforcement. The funding will also be used to update information systems like phone applications, websites, and hotlines.

Klinger believes legislators should prioritize student-focused prevention measures, such as structuring a safe environment, being more personally attentive to the students, and educating on all issues from mental and physical health to crisis planning.

She says the money is typically used instead for “target-hardening,” which refers to increased security measures, such as metal detectors, law enforcement officers, cameras, and “run, hide, fight” training. In Klinger’s opinion, these strategies are quick fixes. Some researchers think target-hardening methods can send the message to students that school is a dangerous place, or that they are not trusted.

“Run, hide, fight” is an active shooter safety protocol promoted by the Department of Homeland Security that says a person’s first defense should always be to evacuate if possible. If not, the next step would be to find a safe and quiet place to hide. As a last resort, only when one’s life is in imminent danger, should they consider using physical aggression.

Klinger’s organization prefers an all-hazards approach, which provides training for a variety of possible occurrences—not just an active shooter. She explains, while the organization does provide training options for active shooter response, these events are statistically less likely to occur than many other dangerous incidents, such as traveling to and from school, getting sick from germs at school, or suffering a severe athletic injury.

The emotional impact of publicized school shootings can cloud out the true likelihood of these events occurring, especially when they happen as often as they have in recent months.

Klinger describes school safety as being not just about active shooter response or increasing security in schools, but about knowing who is at risk for violence against themselves or others. The ESSN engages schools in threat assessment to determine when a student might be at risk of harm. The threat assessment model is based on facts, as well as behaviors and concerns—not on stereotypes or assumptions.

The organization also instructs schools on strategic supervision, or everyday practices and procedures that can prevent violence. They stress the importance of creating a culture where students feel safe and have trusted adults they can bring their concerns to.

Schools across the country are developing individualized strategies for accomplishing this goal. Part of the target-hardening method, Kate Dudlak is a corporal police officer who worked part time as a guard for Edison Jr./Sr. High School in Lake Station, Indiana, this past year.

Her job included standing watch during lunch periods and patrolling the halls, constantly making sure all outside doors were locked. More importantly, though, she says she was there to build rapport with the students—to establish a connection with them, so they’d feel comfortable coming to the officers if something was wrong.

Dudlak believes it’s important for students to understand the officers are not there out of mistrust for the students, but to get to know them and to protect them. They are there to enforce laws, not school policy.

Much like the threat assessment model enforced by Klinger and the ESSN, getting to know the students allows Dudlak and other officers to be more in-tune with and ready to confront red flags.

Building relationships, maximizing student safety, and knowing they make a difference is what an officer’s job is about, says Dudlak. The officers are people, she says—not just badges and guns.

The Future of Protection

In February of 2018, about 200 universities, school districts, national education and mental health organizations, along with more than 2,300 experts endorsed a “Call for Action to Prevent Gun Violence in the United States of America” on the University of Virginia website.

The document stresses the importance of adequately screened staffing—counselors, mental health professionals, and social workers—to provide services for those who might be at risk of causing violence.

It incorporates several of the strategies discussed by Klinger and Dudlak, such as maintaining physically and emotionally safe conditions and establishing a national requirement for schools to assess their climates. Likewise, it encourages the establishment of national threat assessment teams and community programs. The document also explores intervention options for individuals who express a strong potential for violence.

Klinger and Dudlak, as well as Heather, feel the future of safety in schools comes down to preventing catastrophic events instead of waiting for them to happen.

Times have changed since Heather first entered the world of teaching: Parents, teachers, and students alike feel increasing distress about attending school. Heather expresses immense gratitude for the courageous and fast-acting Jason Seaman, who saved what could have been multiple lives, and for her son’s teacher, Mrs. Higgie, who communicated with parents in real time throughout the ordeal. The Noblesville community is fortunate to have leaders like these, she says, but it’s not in their contracts to put themselves on the line.

This isn’t something we should be arguing about, Heather says. Instead, she believes schools can only become safer through working together toward a solution.