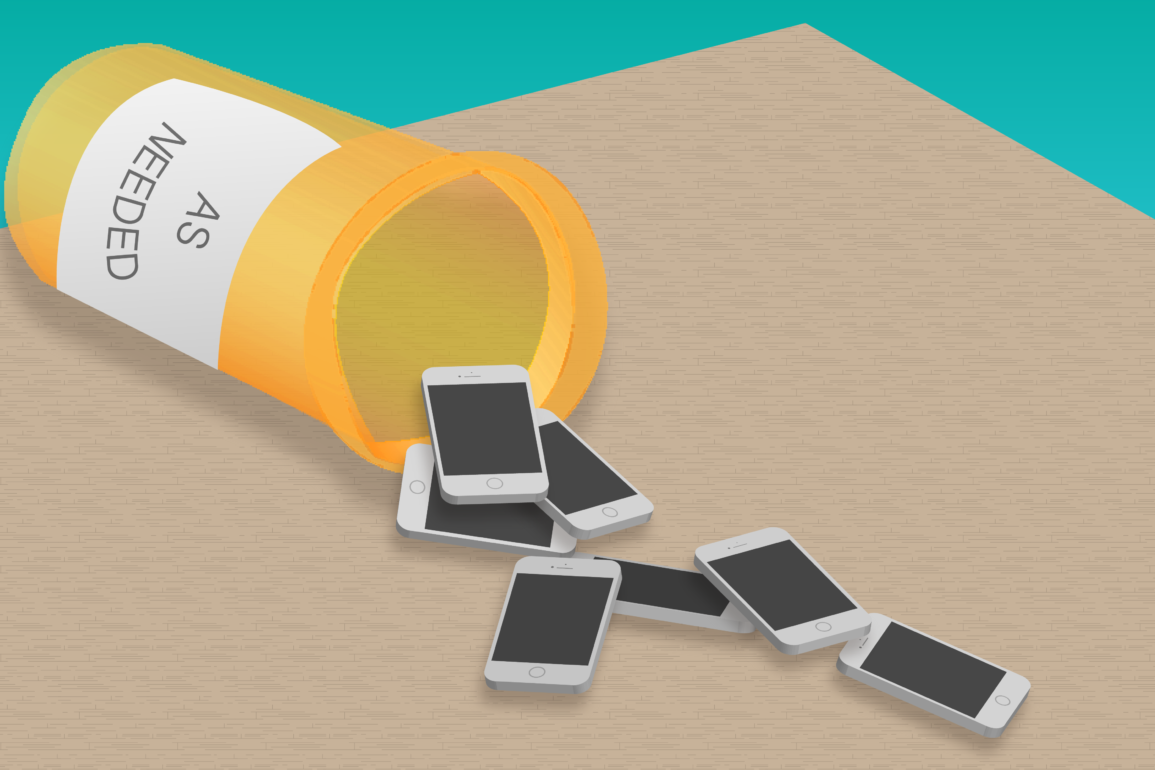

Mental health apps allow for users to seek temporary help, but shouldn’t be sole treatment.

Amanda Barber, a teacher at Walker Elementary in West Allis, Wisconsin, practices active brain breaks with her students multiple times a day. This routine involves following meditation instructions and breathing activities from apps like Go Noodle, a mental health website and smartphone app. Teachers at the school began using the program a couple of years ago to help students practice mindfulness in the classroom.

Mental and emotional health are important to the administration at Walker Elementary, so students also receive 30 minutes of counseling each week for social/emotional learning (SEL). This serves as an elective class similar to music or art. They want students to know that their mental health is just as important as their physical health.

Amanda’s class is young—kindergarten and first grade—and she still wonders how much Go Noodle actually does for their mental health. She says programs like this might be helping her more than the children. When she closes her eyes and her whole class takes a deep breath, Amanda feels more ready to finish her day than before Walker Elementary prioritized mindfulness.

After learning what mindfulness can do for mental and physical health, as well as seeing what it can do in a classroom, Amanda decided to try a mental health app for herself. She used Go Noodle at school for a couple of months before downloading Smiling Mind to use at home.

Developing a Mental Health App

David Bakker, a clinical psychology student, has always had a passion for technology and how people use it. In his final year of pursuing his doctorate, Bakker worked with Nikki Rickard, an associate professor at Monash University in Australia, to create the mental health app Mood Mission.

Bakker says psychologists in Australia use Internet Cognitive Behavioral Therapy. It’s a type of psychological therapy that has the most evidence for being effective in treating problems ranging from anxiety and depression to gambling and insomnia. It can reduce, or sometimes eliminate, time spent in person with a clinician. Internet Cognitive Behavior Therapy was the beginning of using modern trends and technology to help people when they’re feeling low. By using the internet and computer technology to provide therapy, psychologists were able to adapt the strategies to mobiles apps.

However, online therapy has a bigger appeal than just its innovation. Bakker says people like the accessibility of online or in-app therapy compared to traditional treatment. Sometimes individuals who should be seeking help for stress or mental illness have difficulty finding the time or effort to go see a professional in person. Some people can’t afford regular therapy sessions, and others might not want people to know they are going to therapy at all. App-users can access help whenever they want and they can choose to keep their treatment private.

For Amanda, the appeal of a mental health app was wanting to have a mindfulness routine at home since she already had one at school. Smiling Mind was free, and like Mood Mission, allowed Amanda to work on her mental health without having to seek traditional therapy.

Amanda spent an evening researching the options for free mental health apps. She decided against dozens of other apps when she found they were initially free, but charged fees later on for access to several features. Amanda eventually chose Smiling Mind because she likes how in-depth its treatment is for a free mental health app.

How They Work

Bakker’s app, Mood Mission, is meant to help people deal with stress, low moods, and anxiety. The app measures someone’s well-being over time, keeping records to inform its treatment suggestions. This data includes things like how often people feel sad or anxious and what strategies help lift their moods.

Bakker says Mood Mission is an in-the-moment app. When people feel stressed, they tell the app by selecting the choice that matches their mood. The app then provides five different strategies the person could use to feel better.

These strategies come from a database of 200 options. If someone tells Mood Mission about feelings of anxiety, nervousness, or worry, the app describes how that feeling affects the body. If the person’s feelings are making it hard to accomplish something, Mood Mission suggests options to get started: write a blog post, visit a favorite website, prepare lunch, etc. The app also explains why certain activities should help with someone’s current mood. Mood Mission asks users to rate their feelings again after completing the activity so it can keep track of which strategies do and don’t work for a user.

Bakker says it works a bit like Netflix—the more you use it, the better suggestions you get.

After her daughter was born, Amanda struggled with anxiety and was eventually diagnosed with general anxiety disorder. Her mindfulness routine helps with her anxiety. When she records her feelings on Smiling Mind, the app guides her through a meditation activity to lift her mood.

Bakker says, unlike Mood Mission and Smiling Mind, other mental health apps sometimes claim to replace a therapist or even cure mental illness.

Smiling Mind and Mood Mission make it clear that users shouldn’t consider app use as a cure for mental illness or a replacement for a regular therapy.

That’s why Mood Mission publishes the research they use to maintain the app, Bakker says. Bakker and Rickard want users to understand how the app works. They also let people know about strategies that aren’t working so well, aiming to improve in the app’s next update.

An App is Not a Person

Upon first opening the Mood Mission app, users see a screen that says, “Mood Mission is not a replacement for professional help.” And Bakker says no mental health app is.

Bakker believes the best treatment for people with mental health issues is in-person therapy. Apps are designed for a broader audience than just people with mental illnesses, so this form of treatment probably wouldn’t be specific enough to help most people with disorders like depression and anxiety.

While Amanda loves that Smiling Mind is in-the-moment, the mood-lifting strategies don’t fully relieve her anxiety. She says it can’t replace the face-to-face interaction of visiting a therapist, which she does twice a month. But she usually keeps quiet about her treatment—she wants to avoid the negative stigmas sometimes associated with needing therapy.

Those stigmas cause some other people who need therapy to neglect seeking help altogether. Nearly two in three people who have been diagnosed with a mental health disorder don’t seek treatment, according to the World Health Organization. Bakker believes that if mental health apps can reach those who aren’t getting help, their goal is accomplished.

For Amanda, it’s just another way to stay mindful of her mental and emotional health.