During his first year in grad school, Quintin Cooper stood in position for the next play against the University of Toledo. He spotted the quarterback throwing the ball to the receiver and started running down the line. He prepared to stop the opposing receiver from making a touchdown.

After hitting the opposite player, Cooper fell to his knees and blacked out for a few minutes. After he gained consciousness, he walked to the sideline and tried to remember where he was.

“What hotel did we stay in?” He remembers thinking to himself. “What did I eat this morning?”

The team went to the locker room, where Cooper performed two tests.

First, Ball State athletic trainer Shawn Comer swayed his finger from left to right in front of Cooper’s face. Next, Cooper tried the balance test. He closed his eyes and attempted to stand on one foot to maintain balance.

He failed both tests and sat out for the remainder of the game.

This would be the second time Cooper experienced a concussion. The first being his senior year of high school.

He had a headache after colliding with a player from the opposing team. He walked over to the sidelines and approached his coach, not realizing the severity of his headache.

Wanting to stay in the game, Cooper went back on the field for the kick return. When the ball landed in front of him, he blankly stared at it, incapable of processing what happened. Seeing the incident, the referee stopped the game and escorted Cooper off the field.

During his first year in grad school, Quintin Cooper stood in position for the next play against the University of Toledo. He spotted the quarterback throwing the ball to the receiver and started running down the line. He prepared to stop the opposing receiver from making a touchdown.

After hitting the opposite player, Cooper fell to his knees and blacked out for a few minutes. After he gained consciousness, he walked to the sideline and tried to remember where he was.

“What hotel did we stay in?” He remembers thinking to himself. “What did I eat this morning?”

The team went to the locker room, where Cooper performed two tests.

First, Ball State athletic trainer Shawn Comer swayed his finger from left to right in front of Cooper’s face. Next, Cooper tried the balance test. He closed his eyes and attempted to stand on one foot to maintain balance.

He failed both tests and sat out for the remainder of the game.

This would be the second time Cooper experienced a concussion. The first being his senior year of high school.

He had a headache after colliding with a player from the opposing team. He walked over to the sidelines and approached his coach, not realizing the severity of his headache.

Wanting to stay in the game, Cooper went back on the field for the kick return. When the ball landed in front of him, he blankly stared at it, incapable of processing what happened. Seeing the incident, the referee stopped the game and escorted Cooper off the field.

The athletic trainer took his helmet and told him he was not going back in the game.

“When I first got my concussion in high school, I really didn’t know what to expect,” Copper said. “I thought your head hurts for a minute and then it goes away.”

“When I first got my concussion in high school, I really didn’t know what to expect,” Copper said. “I thought your head hurts for a minute and then it goes away.”

The concussion left him in a foggy state of mind and incapable of remembering his birthday or his name.

Cooper is part of the 5 percent to 10 percent of athletes who will have a concussion in their lifetime, according to Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In one game, an athlete has a 78 percent chance of walking away with a concussion.

Dr. Guatam Phookan, a neurosurgeon at Ball Memorial Hospital, said whether it is minor or severe, there are about 3 million sports-related concussions per year in the United States.

“A lot of them are football related,” Phookan said. “American football has a high-incidence of concussions.”

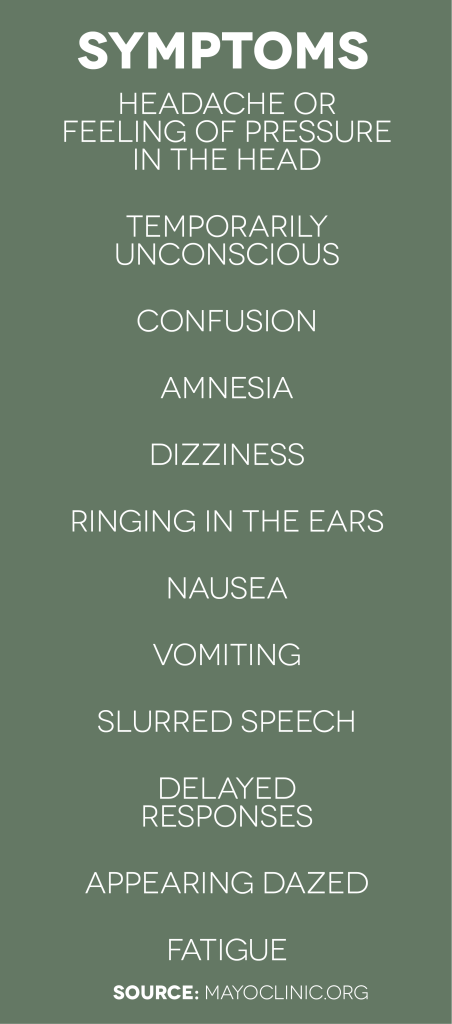

Cooper’s first concussion in high school is classified as a grade two, Phookan said. He experienced amnesia, but did not black out. Grade one is someone who has minor symptoms of a concussion but does not include amnesia or lost consciousness. Grade three, which is the highest, is loss of consciousness.

On his second concussion, Phookan said Cooper was at this level. Grades are based on amount of time an individual experienced amnesia or consciousness.

Cooper said after his first concussion in high school, he researched the condition.

“I knew what to expect,” he said. “[I took] it more serious.”

The severities of a concussion determine whether or not an athlete needs to go to the hospital.

The CDC said emergency visits increased from 153,375 in 2001 to 248,418 in 2009. The number of concussions among college football players had doubled, said WebMD. But one reason the numbers increased is because the awareness of concussions went up.

Dr. Robert Cantu, clinical professor for the department of neurosurgery at the University School of Medicine in Boston, said in a New York Times article that talking about concussions helped increase the awareness.

“I view the numbers as encouraging. Some people will say that the numbers go up because the number of concussions is going up, but I don’t believe it,” Cantu said.

However, there are a large number of concussions underreported. Dr. Phookan said more than half are still not counted for.

![]() “As a nation, we need to take it seriously,” he said. “It moves us all to pay close attention to the epidemic of concussions.”

“As a nation, we need to take it seriously,” he said. “It moves us all to pay close attention to the epidemic of concussions.”

Phookan said recovery time varies by the level of the concussion. However, if a person has another one without fully recovering, they are at risk of developing the post-concussion syndrome. This happens when an individual eventually recovers, but still has symptoms such as headaches, memory loss and trouble completing every day tasks.

A week after his second concussion, Cooper took a memory test. He did not pass and had to sit out for the next game. Cooper played the following game after passing a second test. He said it was great being back out on the field with his teammates, whom he calls his brothers.

Recovering from his concussion made him understand the significance of taking action.

“[Concussions] are serious and if you have [one], maybe go see a doctor right away,” Copper said. “Take necessary steps to make sure that [it] doesn’t get worse. Don’t wait because you could mess up your whole life.”