Organ donation: Easy to get involved. Easy to save a life.

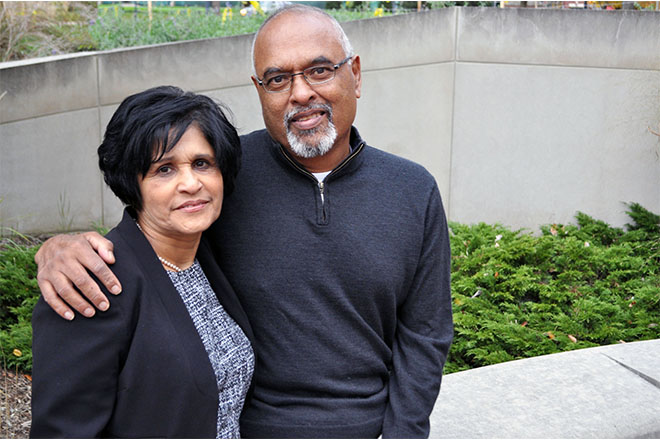

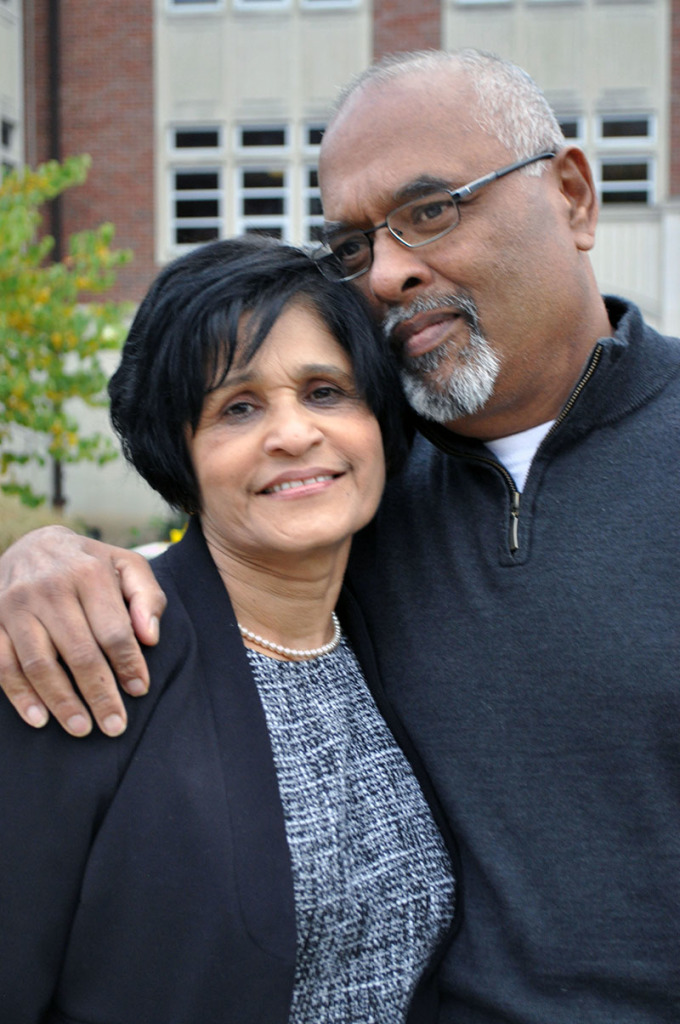

Husband. Father. Grandfather. Professor. Diabetic. All these words describe Srinivasan Sundaram, a Ball State finance professor, who has been diabetic for 33 years. In his first semester teaching at Ball State in 1991, he had a triple bypass, an open-heart surgery in which blood vessels are taken from one part of a person’s body and transferred to heart vessels to prevent blockage.

Sundaram, who suffered kidney failure, underwent dialysis treatments, which are typically over three hour treatments, three days a week. Dialysis treatment can destroy a person’s veins, which makes the procedure more difficult. He would sometimes go in for treatment, but would be sent home because the medics could not access his veins.

Along with treatment, Sundaram faced many dietary restrictions. According to the National Kidney Foundation, patients on dialysis need to eat more high-protein foods, fewer high-salt, high-potassium, high-phosphorus foods and learn how much fluid they can safely drink.

“End stage kidney disease can be very isolating since dialysis and transplants are the only treatment options,” said Janine Moore, the development director of NFK Indiana. “The most common form of dialysis, in-center dialysis, must be performed three times a week for three to five hours per treatment—that’s a part-time job.”

This leaves people like Sundaram, who work and do dialysis, with little opportunity for travel and hobbies.

Three years ago, Sundaram realized he would need a kidney transplant. He was put on two waiting lists: the cadaver list and the diseased donor list. On the cadaver list, Sundaram could receive a kidney from a deceased donor. On the diseased donor list, he could receive a kidney from a person with other medical complications, such as an HIV patient.

According to the Living Kidney Donor Network, there are over 80,000 people on the kidney transplant waiting list. Every year, 4,500 people die, waiting to receive a kidney.

Organ transplantation is used as a medical treatment for end-stage organ failure, according to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Every day, an average of 79 people receive organ transplants, while an average of 18 people die waiting for transplants due to the shortage of organ donors.

Even with the extensive amount of time dialysis takes, some patients are resistant to receiving an organ transplant.

“There were people on dialysis I used to talk to and say ‘Are you on the transplant list?’ And it was like if I was speaking Greek,” Sundaram said. “Some of them just said ‘no, I’m not going to have somebody else’s body part in me.’”

The Sundarams’ two children wanted to donate their kidneys to their father. He refused. But when Kaveri Sundaram, Srinivasan’s wife, stepped up to offer hers, he could not fight her on it.

“God has made everybody,” said Kaveri. “Whose kidney, whose organ… it doesn’t make any difference.”

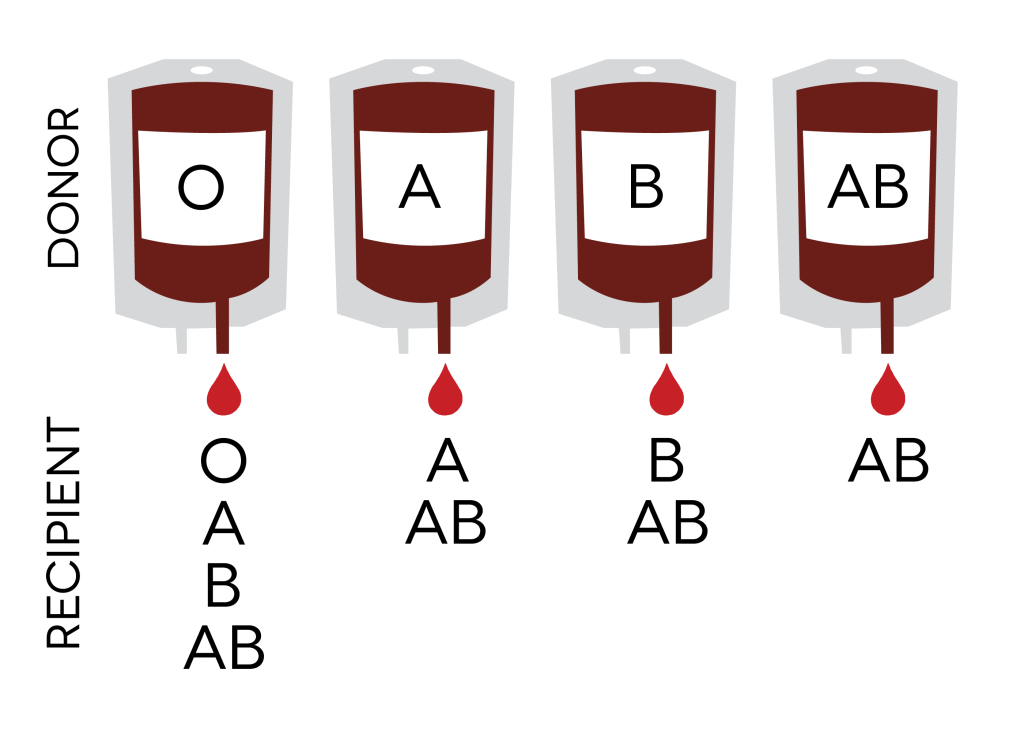

The two underwent various tests to ensure that they were able to donate and receive kidneys. Unfortunately, the two have different blood types, so Kaveri’s kidney could not go to her husband. Although she couldn’t donate a kidney to her husband, she still donated it to a recipient in Atlanta.

The process of finding a donor works as a series of matches. The Sundarams sent in their names and blood types, and a computer matched them to other donors and recipients. Srinivasan received offers from two different donors who backed out later.

Eventually the couple was matched up in a group of six: three sets of recipients and donors.

Srinivasan received his new kidney from a donor in California on July 15, 2014.

According to Mayo Clinic, about 90 percent of people who receive a living-donor kidney transplant and about 82 percent of people who receive a deceased-donor kidney transplant will live at least five years after their transplant.

Which blood types can be donated and received:

Both Sundarams had successful surgeries at Indiana University Hospital in Indianapolis. Kaveri was allowed to come home after three days in the hospital, while Srinivasan came home after six.

Kaveri admits she didn’t know much about what it takes to donate a kidney until her family was put in this situation. Both she and her husband feel that the reason so many people do not donate organs is because they are not informed.

“You have two kidneys,” Kaveri said. “Out of that you need only 30 percent of one kidney. So you’ve got 170 [percent] left there. If somebody’s dying, why can’t you give? That was my idea.”

On April 25, 2014, Maria Williams-Hawkins, an associate professor of telecommunications at Ball State, held a march for finding the “perfect match” to promote donation awareness. At the event, Srinivasan met Moore.

After speaking with Moore and Williams-Hawkins, Srinivasan is now trying to spread awareness and reach out to Muncie citizens to become organ donors.

“I spent a lot of time talking to the organ procurement office and I found out that Muncie was the worst city in the state with regard to organ donation and transplantation,” Williams-Hawkins said.

Williams-Hawkins arranged for Srinivasan to speak at various churches around Muncie to spread awareness.

Srinivasan is aware that stepping up to give a kidney is intimidating and that it’s very rare for a person to walk up to a hospital and donate an organ, especially without the proper knowledge.

If Srinivasan and Kevari had not been educated, two lives could have been lost.