Zach Roach sits back on his couch, his tone sounding somewhat annoyed. He, like many others, is tired of hearing about the Ebola virus from every mass media source in America. He said he thinks it’s being used to create fear in people who know little about the disease.

“Sure, it has the potential to spread, but no, I don’t have any fear,” Roach said. “There have been cases already, and with something like Ebola, I think that if it were going to spread, it would have spread already.”

Roach, a Ball State junior, is one of many Americans who have stopped taking the Ebola epidemic in West Africa seriously, because he thinks it has been sensationalized and blown out of proportion.

“I think [for Americans] Ebola is more of a deterrent to real problems,” Roach said. “So it’s an epidemic in that case. It’s a social epidemic, but not a medical epidemic.”

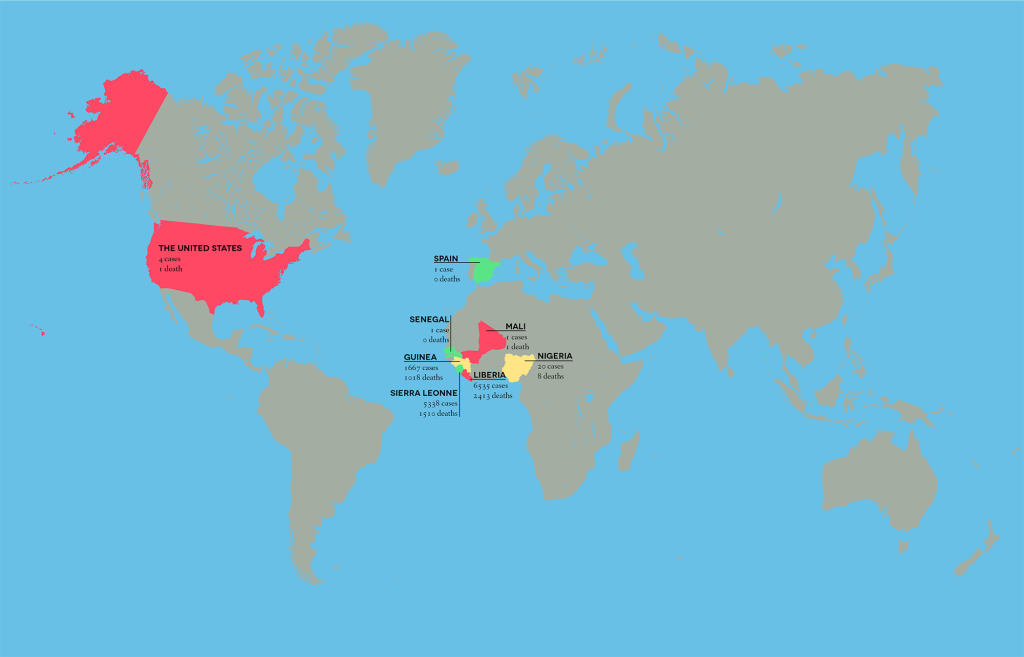

In October, Reuters reported that the Ebola virus broke out in Africa sometime last March, with cases sprouting up in seven countries in the following months.

Since then, the epidemic has attracted immense concern from Europeans and Americans, becoming a regular feature for headlines and breaking news stories from around the world.

The Centers for Disease Control has confirmed four cases of Ebola in the U.S. since October, causing panic among Americans who know little about the disease other than its high mortality rate.

The World Health Organization estimated that 70 percent of Africans who contract the virus die, but this doesn’t apply to all areas, including the U.S.

Polls conducted in October by The Washington Post and ABC News showed that two-thirds of Americans fear a widespread Ebola epidemic in the U.S. and believe that the government should take more preventative measures before the situation worsens.

Some students, however, have more optimistic feelings about the epidemic. Ball State sophomore Kevin Krauter said he isn’t worried about the disease in America.

“We’ve seen that the disease is treatable, and that people have had the disease and come to America and have been cured already, so I have faith in the American medical system,” Krauter said.

Jagdish Khubchandani, who has a Ph.D. in health education, is an associate professor of community health education at Ball State, specializing in world health and clinical epidemiology.

According to Khubchandani, strains of Ebola have actually existed in Africa since the late 1960s, and small outbreaks have happened in several countries across the continent since then.

He said that while the number of cases today is higher than it ever was in the past, the strain spreading across Africa right now isn’t any more dangerous than the ones that came before it. He said that the real problem with the epidemic is how the governments are handling it.

“I don’t think it’s a battle against the virus,” Khubchandani said, “For me, it’s a battle against the fragility of health care systems that we have in the modern days.”

Khubchandani said that in vulnerable countries, health care has been compromised since the original outbreaks. As populations and poverty have increased, the established systems have not adapted to meet the people’s needs.

The lack of containment is because of the drastic shortage of doctors, nurses and equipment in the afflicted countries, he said. The conditions are not likely to improve because the resources to support them aren’t there.

“I think the governments have to believe that until they essentially take deep interest in their population’s health, nothing will change,” he said.

In response to this problem, the United Nations sent representatives to West Africa in September to help create an infrastructure for medical care in the governments of the affected countries, according to an article in the Huffington Post.

The article says their efforts were criticized because their response to the epidemic came six months after it actually began. Also, they provided very little actual resources, like medical equipment and staffing.

Ken Isaacs, vice president of the humanitarian aid organization Samaritan’s Purse, commented on the U.N.’s handling of the situation in an interview with the Washington Post by asking, “Why would the world allow what is potentially a global epidemic to be managed by three of the poorest countries in the world?”

While statistics have shown that the situation in West Africa is worsening, Khubchandani there are steps that can be taken to fight the problem.

Khubchandani sees three necessary improvements that need to be made before this epidemic and others like it will stop happening in Africa. These include lowering the cost of medical care, raising the quality of medical care and gaining more widespread access to these resources for the people who need it.

He also said that if Westerners do nothing to help make these changes, the consequences will extend beyond Africa.

“The fact that we could not protect people from Ebola in Africa is now affecting other countries, other people,” Khubchandani said. “It kills economies [and] creates unnecessary healthcare expenditures.”