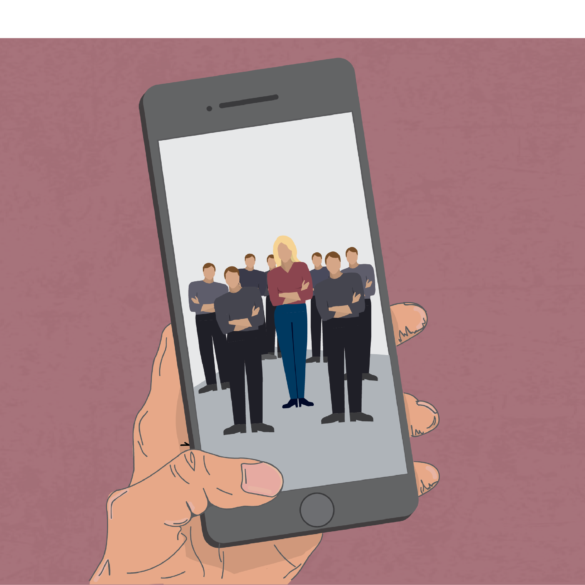

Despite the issues women can face in male-dominated fields, the technology field is slowly progressing and becoming more diverse.

Becky Hammons was 36 years old when she decided to have her second child.

She had started working at Apple about five years prior, when she was 31 and a single mother to a 6-year-old. She was in the network and communications division of the research and development team, which she knew to be predominantly male. What she didn’t know or expect was how the men in her department would react when she was visibly pregnant.

How did you decide it was okay to get pregnant? one male co-worker asked her.

With that question, Becky knew what the man was really saying: Their work was their life, and for her to choose to have a child while continuing to work was desirable but terrifying all at once.

To her, their questions about her work performance became a challenge. Throughout the pregnancy, Becky continued to do her work efficiently and held her leadership role in her department.

Catalyst, a global nonprofit that works with CEOs and companies to create workplaces that work for women, defines a male-dominated field as a field that is composed of 25 percent or fewer women. Those same industries are prone to falling into masculine stereotypes, and those stereotypes make it significantly harder for women to excel in the company.

Despite this, women don’t face “struggles” in these environments, according to Kirsten Smith, the associate director of the Center for Information and Communication Sciences (CICS) at Ball State University and a chairperson for Women Working in Technology, an organization that hosts an annual conference at Ball State. Smith and Becky prefer to use the terms “issues” or “challenges” to describe what women encounter that men don’t in these work environments. They often have to figure out how to overcome those challenges.

It Depends On Where You Live

Becky says the challenges women face in the technology field vary depending on where the employee lives. For Becky, multiple opportunities have opened up which have allowed her to witness these challenges in several cities and states.

While she was a sophomore at Michigan State University, Becky was offered a position at the United States Air Force Research Station. She worked there about 25 to 30 hours a week until she graduated in 1977 with her bachelor’s degree.

In the population of workers she surrounded herself with, Becky can only remember one other woman.

When she graduated, she was offered a job at a small tech company in Ann Arbor, Michigan. She stayed there until 1979, when she was offered a position in San Antonio. Next, in 1986, she was offered a position at Apple in Cupertino, California. She worked for Apple for 11 years, even moving to Austin, Texas, in 1992 for the job. She decided to leave Apple in 1997 and move to Indiana, where she has stayed since.

Each city has its own environment and culture, and Becky witnessed that firsthand. The bulk of discriminatory behaviors Becky faced were in Texas and California. She says those were early years for the industry, so less attention was given to those abuses in the workplace.

When she lived in San Antonio, there was a law that people couldn’t buy pantyhose on a Sunday. It was an extremely conservative community, which was completely different from 80 miles away in Austin.

In California, multiple co-workers looked at her like she was crazy for having children.

Why don’t you just get a dog? they’d ask her.

California is known to be a liberal and open state, but Becky says while she was there, that liberal thought process didn’t feel present in the corporations. She considered most companies to be conservative and male-dominated.

She says in Indiana in 1997, it was an embarrassment for men if their wives had to work.

“The stay-at-home wife was the badge of success in Indianapolis in the years that I worked there leading groups,” Becky says. “That was always interesting to me because I couldn’t understand why a college-educated wife would want to stay at home full time.”

There might be many reasons a woman chooses to stay home rather than work, but the tech subculture maintained the idea that men made good money so their wives didn’t have to work.

It Starts Young

Becky desperately wanted to be a writer when she was a young girl.

Her maternal great-grandmother was her role model. Born in Toronto, her great-grandmother taught herself seven languages, painted, and was a writer herself.

Becky wanted to follow in her footsteps, so she went to college for an English degree.

But when Becky was offered the position at U.S. Force Research Station, she noticed how her degree could transfer into the technology and communications field, and she enjoyed the two fields, so she chose to stay in technology.

In the media, women are more likely to be shown in teaching, clerical, service, and professional jobs. Smith says this is etched into girls’ minds at a young age.

That issue is a cycle, according to Smith. Young girls don’t have a role model to look up to in “masculine” fields, so they often don’t pursue those fields. Then, because they don’t do that, there aren’t role models for the next generation to look up to, and so on.

Ambivalent sexism is a theory stating that sexism has two components: hostile sexism and benevolent sexism. Benevolent sexism is when one gender presents qualities or actions to another gender that could potentially appear “subjectively positive,” but in a broader spectrum are actually more damaging to gender equality.

Smith says benevolent sexism is the result of teaching boys and girls that women are to always be treated respectfully and with kindness, which can ultimately lead them to not treating women equally. Benevolent sexism is very common in male-dominated environments, Smith says.

According to the Economics and Statistics Administration’s 2017 Women in STEM report, in 2015, women filled 47 percent of jobs in the U.S., but only 24 percent of STEM jobs.

There are various reasons why women have been known to stray from male-dominated fields. Those issues are lack of awareness, performance settings, backgrounds, and the prioritization of other life areas, according to the Cornell HR Review.

Becky also agrees that the technology field is becoming a lot more diverse than it was when she first started.

It’s Difficult to Overcome

Smith says many factors can affect whether women are treated with fairness and equality in the workplace. One of those factors is pregnancy and motherhood, which Becky witnessed firsthand.

In 1991, while Becky was working for Apple, the company was undergoing a lot of restructuring. While she was pregnant, her department was placed under a new male boss.

When it was getting closer to Becky having her second son, she says the man was “okay” with her being pregnant, but he didn’t want her taking maternity leave.

You should not expect to take any time off when you do have the baby, he told her. You need to promise to come back as soon as possible.

That wasn’t the only sexism she has faced during her career. In 2001, Becky was working for a tech company in the heart of Indianapolis under a man she describes as “not a stable person.” She had only worked for him for a year when she decided to resign.

While she was working for him, she had a group of younger men working for her who enjoyed the way she led their team. Becky says the man was envious of her leadership and how much her employees liked her. After Becky quit, not wanting to deal with him anymore, he started the rumor that he fired her for having sexual relations with one of her staff members.

“It kind of blacklisted me and followed me for a while,” Becky says.

Eventually, multiple companies realized he was a dishonest man, and he was fired. But the stories still followed Becky for years after the incident.

In 2010, one company reached out to interview her for a position, but she says she ultimately didn’t get the job because the stories the man made up still circulated the industry.

It’s kind of hard to prove a negative, but if that’s the way you work, that’s fine, she replied to the company.

Becky didn’t sue for slander, nor did she attack the man back with more made-up stories. She says she would rather sit back and let karma take its course eventually.

“The thing that strong women do is they learn from that,” Becky says, “and they focus on the future and the present, not the past.”

Today, Becky is 62 and is loving her job as an associate professor for CICS at Ball State. This is her first year as a full-time professor, and she hasn’t faced any challenges related to gender.

“I feel like I’ve won the lottery here,” Becky says.