The United States was founded on the principle that anyone could become successful, but this American Dream has proved more difficult for those from lower classes.

Kayla Beeler, a junior at Ball State University, has lived her life in two different worlds.

During her childhood, her time was split between a household that made more than six figures and a household that lived below the poverty line. Kayla’s parents separated when she was around 4 years old. She spent most of her time with her mother’s side of the family. They lived in one home in Hudsonville, Michigan: Kayla, her mom, her aunt and uncle, her three cousins, and her maternal grandparents.

Her dad’s side of the family was a stark contrast.

Although Kayla’s father was sent to prison when she was in elementary school, she still spent some weekends and a majority of her summers with her paternal grandparents. Her grandfather worked as an engineer, and her grandmother was a teacher. They lived in a large home with a private drive in Rockford, Michigan. Kayla says even as a child, she could see the differences between the two households.

Tom Hirschl, a professor of sociology at Cornell University whose research focuses on social stratification, says most people’s lives could be compared to a stock market. You have highs. You have lows. It’s difficult to predict what life can throw at a person.

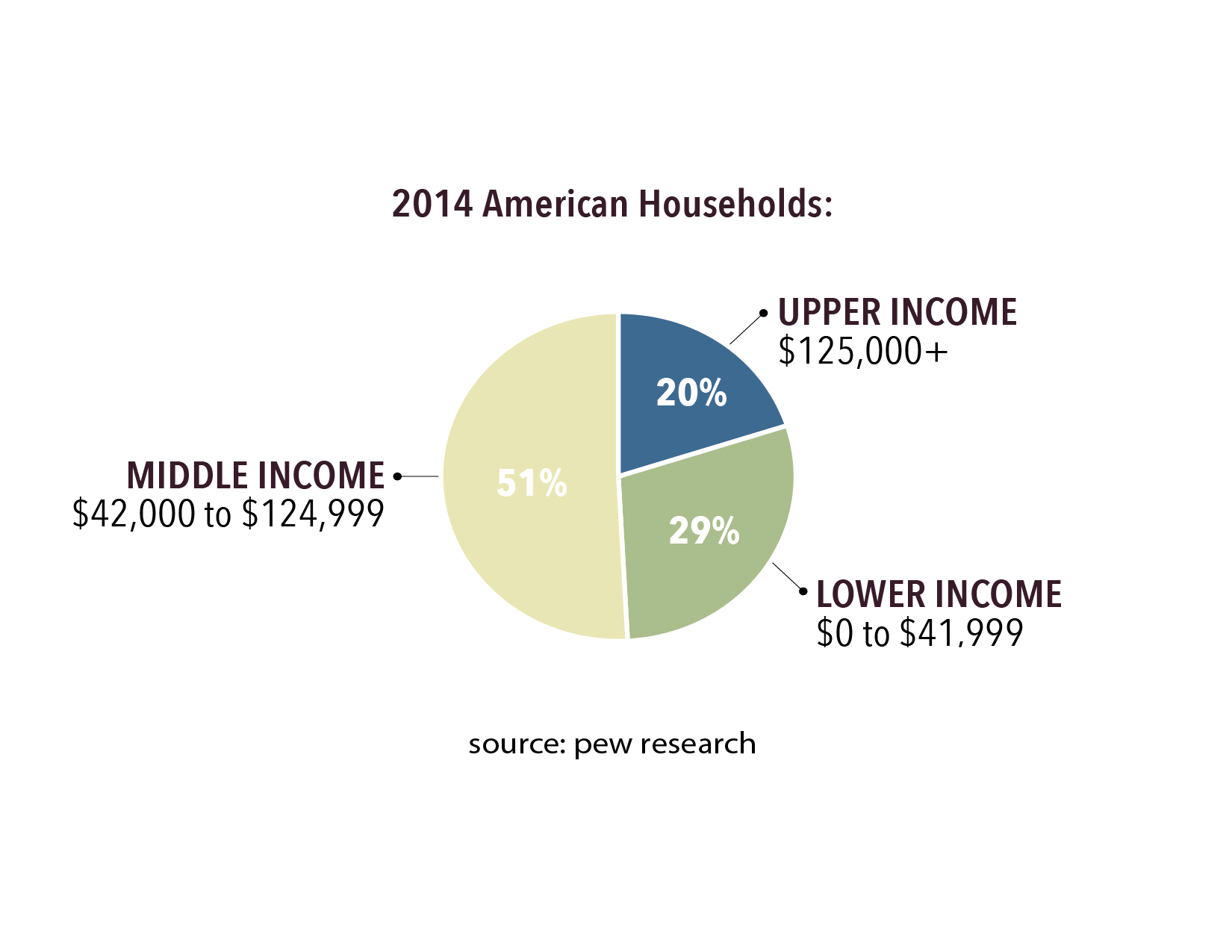

The United States has an economic disparity. As explained by the Council on Foreign Relations, income inequality is significantly higher in the U.S. than in any other developed nation across the globe—even higher than in countries such as Russia or India.

And Americans can feel it. Anger peaked in 2011 during the Occupy Wall Street movement, when protesters in New York City revolted against the country’s economic inequality. A 2012 study by Pew Research Center even found 65 percent of U.S. citizens feel the nation’s income disparity between the rich and the poor has grown in the last decade.

Effects

Economic disparities are most often seen in the everyday lives of individuals, according to a 2015 article published by the American Psychological Association. This is why Paul Piff, an assistant professor of psychology and social behavior at the University of California, begins his course on class differences by asking his students the same questions:

Do you shop at JCPenney or Neiman Marcus?

What kind of car do you drive? Do you even have a car?

What did you have for breakfast? Starbucks? Or Dunkin’ Donuts?

As explained in the article, Piff believes every choice a person makes is somehow affected by his or her economic class.

Kayla’s mom was a waitress at Denny’s and worked third shift every night. Each morning, her grandparents would get Kayla and her cousins ready for school. She says her adult relatives were under a lot of stress, but they kept it hidden from the kids and tried to make their lives as normal as possible. They didn’t have much, but they made it work.

When Kayla was with her father’s side of the family, she wore more stylish, newer clothes. She ate healthier, fresher foods. She could tell the difference between these things, much like Piff explained with his examples.

But she says living with her mom also made her appreciate these “luxury” items more.

Bigger Picture

The social classes individuals belong to can have a larger, long-term impact, as well. A 2009 article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science says class can affect you more than the food you eat or the stores you shop.

Social class affects a variety of factors, including overall health, stereotypes, relationships, and prejudices, according to the American Psychological Association.

For example, the classes people belong to can influence the way they think. In the article from Current Directions in Psychological Science, researchers found individuals from lower-class backgrounds typically rely on others more than those from the upper class.

A 2014 study by the Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin found that people who come from poorer backgrounds are more likely to be influenced by others’ opinions before making their own choices. Study participants from the lower classes often adjusted their own thoughts and choices in order to please others.

People who come from lower economic backgrounds usually do not have the resources or education to make informed decisions by themselves, says Dacher Keltner, professor of psychology at the University of California and co-author of the 2009 article published in Current Directions in Psychological Science.

However, this reliance on others is not necessarily negative. Those from higher social classes are more likely to act independently, but researchers have found this often makes higher-class individuals less empathetic.

Keltner believes those from lower social classes are better at reading people’s emotions, which results in more empathy and generosity.

Kayla’s situation growing up taught her the importance of helping others and giving back, she says. On campus, she is part of Be The Match, an organization that encourages individuals to register with the National Bone Marrow Donor Program. She is also a member of the Sigma Kappa sorority, which helps with a variety of community service projects.

She knows everything could change in a second. So, she wants to help others who might be in tough situations like she was during her childhood.

The American Dream

Since the founding of the U.S., Americans have been told it doesn’t matter who you are or where you come from––if you can dream it, you can do it.

Experts say this conventional wisdom isn’t so true. Research from The Institute for the Study of Labor found the U.S. is one of the most difficult places in the world to achieve social mobility––that is, the ability to move upward toward a more prominent social class.

Education typically plays a large role in an individual’s ability to succeed. The education a person is able to receive often depends on the economic background he or she comes from. According to a 2012 study published by the U.S. Department of Education, only 34 percent of students were considered first-generation––meaning neither of their parents attended college.

Students who do pursue higher education face more problems. As explained by a 2014 research article published by the Association for Psychological Science, first-generation students earn lower grades, encounter more obstacles, and are more likely to drop out than students who have at least one parent who attended a four-year university.

But even an education is not the key to climbing the social mobility ladder. A 2016 study by the Washington Center for Equitable Growth says moving up or down in social class is becoming less and less likely, regardless of an individual’s education level.

Kayla is a hard worker and determined. Her paternal grandparents always told her to study something she would be proud of. She is double-majoring in pre-med and biology and plans to become a surgeon, which has been her goal for as long as she can remember.

Her choice to become a doctor was partly inspired by her love of helping others. It’s also a job where she can easily pay off her stu dent debt and be free of financial burdens.

dent debt and be free of financial burdens.

The upper and lower classes are becoming increasingly different. Hirschl says the U.S. is headed for trouble unless this is fixed soon. F. Scott Fitzgerald, who often dealt with social class issues in his own works, is thought to have once said that “the rich are different from you and me.”

Today, Kayla’s mom is in a better situation. She still works at Denny’s, but she has had a long-term boyfriend for the last several years who works at a factory.

Kayla still has two years of school left before heading off to medical school––she has her sights set on Michigan State University.

Kayla’s childhood taught her a lot. But maybe most importantly, she says, she learned to not judge a book by its cover.

“I want people to know that how you appear externally doesn’t affect who you are internally,” Kayla says. “The social class you belong to doesn’t change who you are as a person.”